The Impact of Service-Learning Classes on Teacher Education Candidates’ Views of Diversity

Jason D. Fruth, Anna F. Lyon, and Alan Avila-John

Wright State University

Author Note

Jason D. Fruth, Teacher Education Department, Wright State University; Anna F. Lyon, Teacher Education Department, Wright State University; Alan Avila-John, Human Services Department, Wright State University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Jason D. Fruth, Assistant Professor, Teacher Education Department, College of Education and Human Services, Wright State University, Allyn Hall 340, 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH 45435. Phone: (937) 775-2636. E-mail: jason.fruth@wright.edu

Abstract

This study examined the impact that a service-learning component in a disability and culture course had on the views of diversity for teacher candidates at a Midwestern university. A group of 96 students took either a treatment course with an additional service-learning component or a control course without the additional component. Diversity scales and qualitative accounts were used as pre- and post-measures to determine the impact of the students’ service-learning experience. The study found substantial differences in the changes in views on diversity between the two groups, especially in relation to views on gender opportunity and teacher expectations.

Keywords: service-learning, diversity, service

It is hardly news that the typical K-12 teacher is White, female, and middle class while student populations have become increasingly diverse; indeed, one has only to walk through almost any public school to draw this conclusion. Thus, a significant challenge for university teacher education programs is how to best prepare teacher candidates for the diverse populations they will likely encounter in schools.

Many teacher candidates arrive on college campuses having had few opportunities to interact with diverse populations (Garmon, 2004; Siwatu, 2006). Delpit (1995) maintained that “when a significant difference exists between the students’ culture and the school’s culture, teachers can easily misread students’ aptitude, intent, or abilities as a result of the differences in the styles of language use and interactional patterns” (p. 176). Service-learning in a variety of settings is one approach to offering teacher candidates opportunities to interact with and better understand others.

Colleges and universities with successful teacher preparation programs often strive to provide teacher candidates with diverse, authentic field experiences early and often in their undergraduate and graduate programs. These experiences present each student with opportunities for reflection and collaboration with fellow teacher candidates, leading ultimately to self-examination. According to Garmon (2004), self-examination is “an awareness of one’s own beliefs and attitudes, as well as being willing and/or able to think critically about them” (p. 205). Active participation in service-learning, along with opportunities for self- examination, may increase exponentially the instances of practical learning for each teacher candidate.

Although it is sometimes said that it is necessary to know one’s self in order to understand others, examination of one’s beliefs and prejudices is often difficult. Even so, self-knowledge is vital for classroom teachers since beliefs may have a high degree of impact not only on how students are treated socially in the classroom and school, but also on how they are taught. As James Banks (2005) stated, “teachers who cannot easily see how their content is related to cultural issues will easily dismiss multicultural education with the argument that it is not relevant to their disciplines” (p. 20).

The addition of a service-learning component to teacher preparation courses—when initiated in an appropriate environment aimed at corresponding specifically with the respective goals of those courses—could provide the authentic, practical experiences that teacher preparation programs seek. Furco (1994) held that service-learning experiences can positively impact particular domains crucial to student growth, specifically academic, civic, personal, social, ethical, and vocational development. Incidentally, many of these domains are consistent with the aims of early field experience within teacher preparation programs.

The authors undertook a study in an effort to gauge attitudes about diversity and service-learning among teacher candidates at an open-enrollment Midwestern university. Most of the approximately 19,000 students enrolled in the university are from surrounding small towns and farms. Minority students make up 17% of the student body, with an additional 5.5% comprising international students representing 66 countries.

The university employs a vice president for multicultural affairs and community engagement whose job is to facilitate the university’s work as it relates directly to multicultural issues on campus, and to promote collaborations with the surrounding community. The desired outcomes associated with this position are “to recruit and retain a student body, staff and faculty who reflect our region and broader global society; to create an environment on campus free from discrimination in which all are invited to participate fully; and finally, to provide members of our campus community the knowledge and skills they need to be productive, successful and engaged citizens of a diverse, global society” (Barret, 2015). While many members of the campus community consider it admirable that the university administration views diversity as an area of focus, it is a challenge to apply and achieve these goals at the individual student level.

Mirroring the national profile, the typical education major at the university tends to be White, female, and middle class. Many enter the education programs with fond memories of their own schooling and with expectations that all schools will offer only minor variations of their own experiences. Often students from small towns and rural areas have had little opportunity to interact with diverse populations; moreover, many have negative impressions of urban schools and of the education students receive in these schools. In contrast, multicultural pre- service teacher candidates are better suited to provide challenging coursework to multicultural students as well as commit to social justice and multicultural teaching (Ladson-Billings, 1991; Rios & Montecinos, 1999; Sleeter, 2001; Su, 1996,1997). Considering the typical education major described above, universities face significant challenges preparing high-quality professionals who are change agents in society.

Despite the homogeneity of education majors at the university level, participation in service-learning by diverse populations can present numerous benefits to all participants. Research and literature on the subject are somewhat limited; however, some attention has been given to uncovering potential advantages of participation in service-learning by students with disabilities. Brill (1994) found that participation in service-learning by students with disabilities can increase social functioning, academic and functional skills, and attendance, as well as foster the development of positive relationships with non-disabled peers. Since Brill only worked with adolescents, further research into this subject could focus on older populations with disabilities, including college and university students. Brill’s information is also dated, limiting its applicability to findings related to this study. Additional research could explore potential advantages of participation in service-learning among individuals from culturally diverse backgrounds, as participants in the current study are mostly White, middle-class, and female education majors.

For this study, a service-learning component was added to an undergraduate course entitled “Introduction to Addressing Learning Differences.” This course provides teacher candidates with a foundation for differentiation related to students with disabilities and students from various cultures. This and other service-learning courses offered at the university are consistent with the insitution’s mission: “We transform the lives of our students and the communities we serve…. We will engage in meaningful community service” (Wright State University, 2015). The university is committed to serving students with physical disabilities, offering, for instance, a series of tunnels that allow easy access to all buildings on campus. The university is also listed on President Obama’s Honor Roll with Distinction for its strong institutional commitment to service and campus-community partnerships that produce measurable results for the region. The aims of the education program, the philosophy of the university, and the lack of experiences with diverse populations among many in the study body led the teacher education programs to the necessity to investigate ways to broaden and deepen understandings.

In this study, 96 teacher candidates enrolled in Introduction to Addressing Learning Differences were asked to complete a diversity questionnaire adapted from Pohan and Aguiar (2001) at both the beginning and end of the course. On this questionnaire, students were asked to provide written responses to qualitative questions about their knowledge, thoughts, feelings, and experiences with diversity and service-learning. They were also asked to indicate their relative agreement or disagreement with a number of statements regarding diversity as adapted from Pohan and Aguiar’s work. These identical pre- and post- questionnaires were administered to students in the treatment course with the service-learning component as well as to a control course utilizing the same instructors and curriculum during the fall term of 2013. The pre-service teacher candidates in these courses were randomly assigned by the typical registration methods of the university. The sole difference between these two courses was the service-learning component in the treatment course (which resulted in shorter in- class time due to the service-learning requirement).

At the conclusion of these courses, pre- and post-questionnaire data were compiled. For the quantitative aspect of the questionnaire, the percent change in agreement with the statements on the questionnaire from the beginning to the end of the course was calculated for both the treatment course with the service- learning component and the control course without the service-learning component. Those changes in agreement were then compared for the service- learning and traditional courses. For many of the items, a distinct disparity in responses was very evident between these two heterogeneous groups. The following figures demonstrate this disparity.

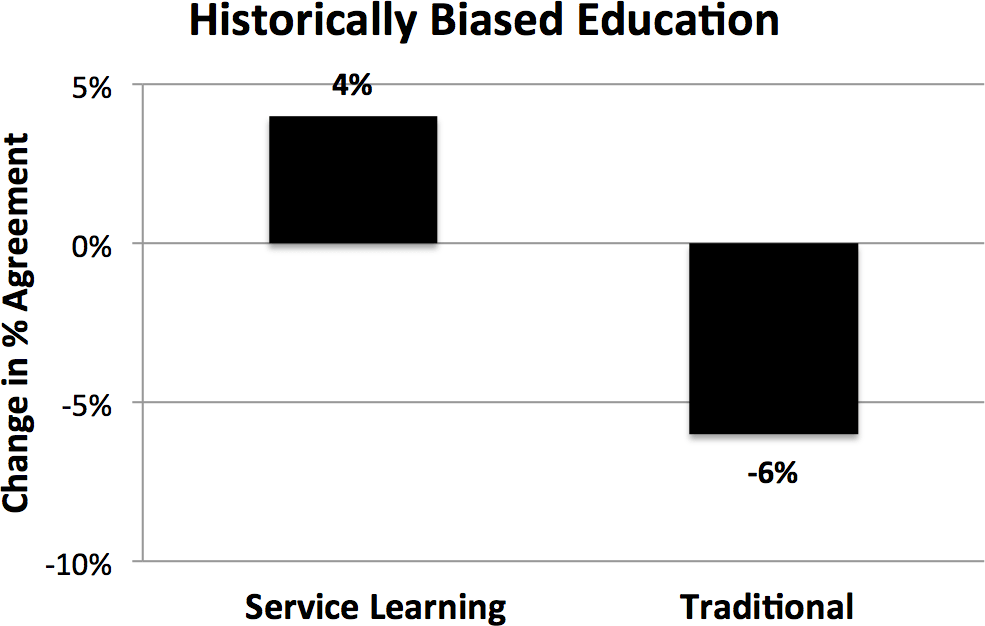

Figure 1 illustrates an increase in agreement within the service-learning course and a decrease in agreement within the traditional course regarding the idea that education has been monocultural and biased toward the European group. Forty-nine out of the 66 (74%) participants in the service-learning course agreed before, while 40 out of 51 (78%) agreed following the experience. Twenty-seven out of the 29 (93%) participants in the traditional course agreed before, while 26 out of 30 (87%) agreed after the experience.

Figure 1. Education has been biased toward the European group.

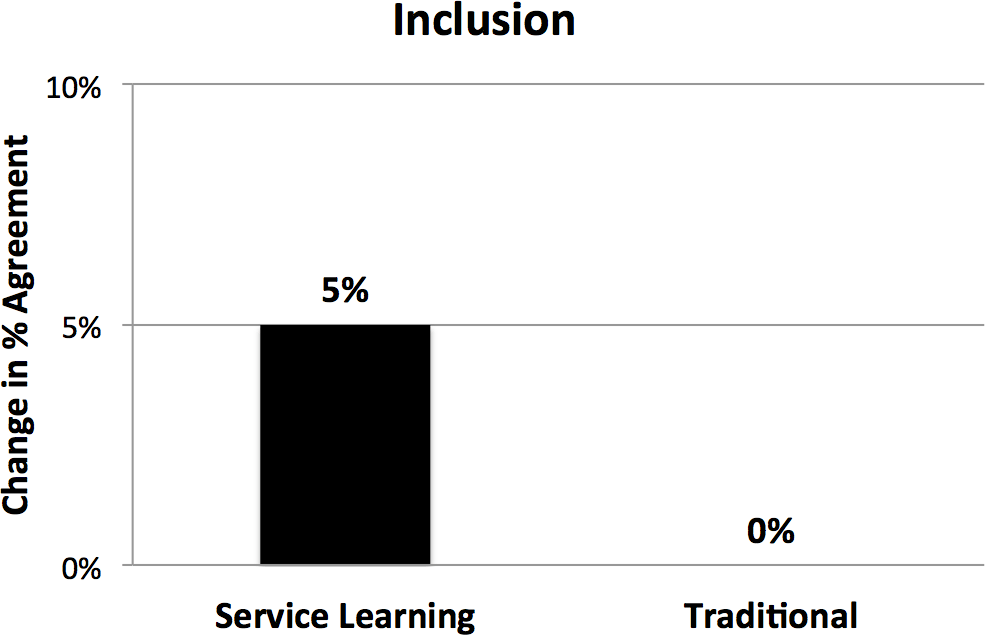

Figure 2 demonstrates an increase in agreement within the service- learning course and no change in agreement within the traditional course regarding the idea that students with physical limitations should take part in regular classrooms when possible. Sixty out of the 66 (91%) participants in the service-learning course agreed before, while 49 out of 51 (96%) agreed following the experience. Twenty-nine out of the 29 (100%) participants in the traditional course agreed before, while 30 out of 30 (100%) agreed after the experience.

Figure 2. Students with physical limitations should be included.

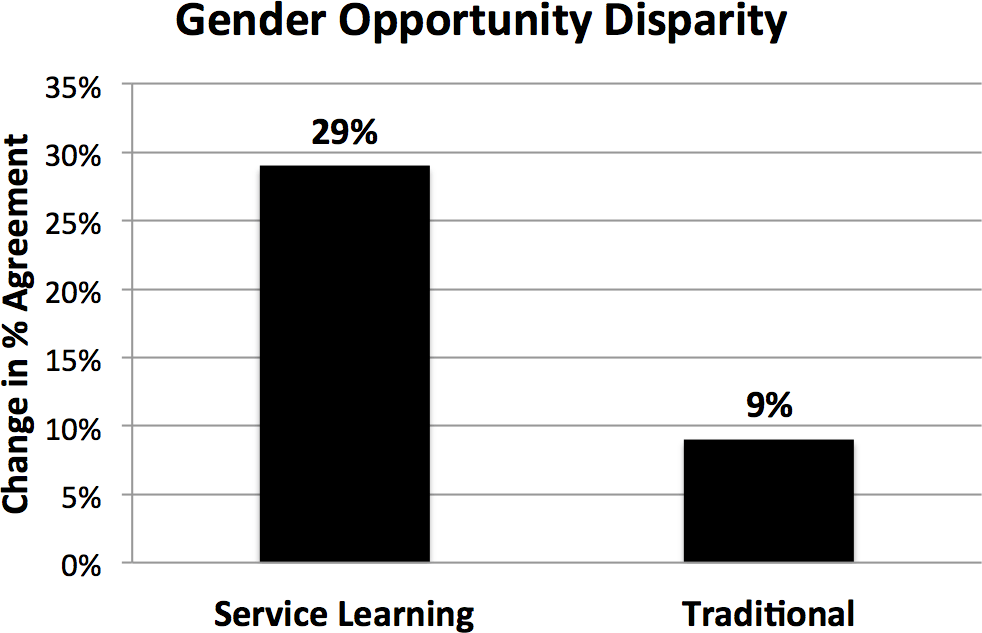

Figure 3 shows a substantial increase in agreement within the service- learning course and also an increase in agreement within the traditional course regarding the idea that males are given more opportunities in math and science than females. Twenty-eight out of the 66 (42%) participants in the service- learning course agreed before, while 36 out of 51 (71%) agreed following the experience. Eleven out of the 29 (38%) participants in the traditional course agreed before, while 14 out of 30 (47%) agreed after the experience.

Figure 3. Gender opportunity disparity in math and science.

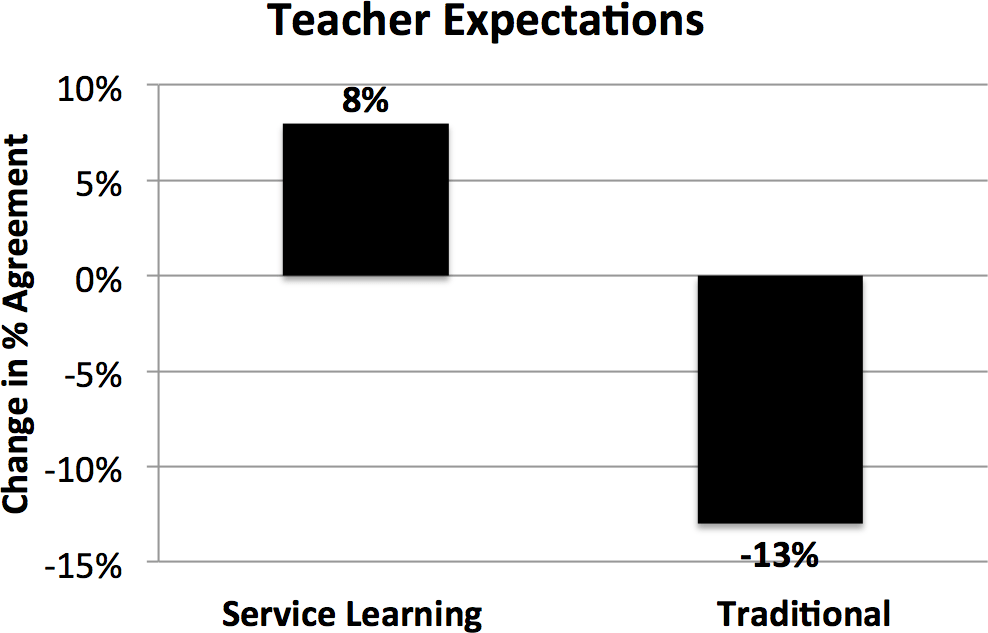

Figure 4 depicts an increase in agreement within the service-learning course and a decrease in agreement within the traditional course regarding the idea that teachers expect less from students from the lower socioeconomic class. Fifty-four out of the 66 (82%) participants in the service-learning course agreed before, while 46 out of 51 (90%) agreed following the experience. Twenty-six out of the 29 (90%) participants in the traditional course agreed before, while 23 out of 30 (77%) agreed after the experience.

Figure 4. Teachers expect less from those from poverty.

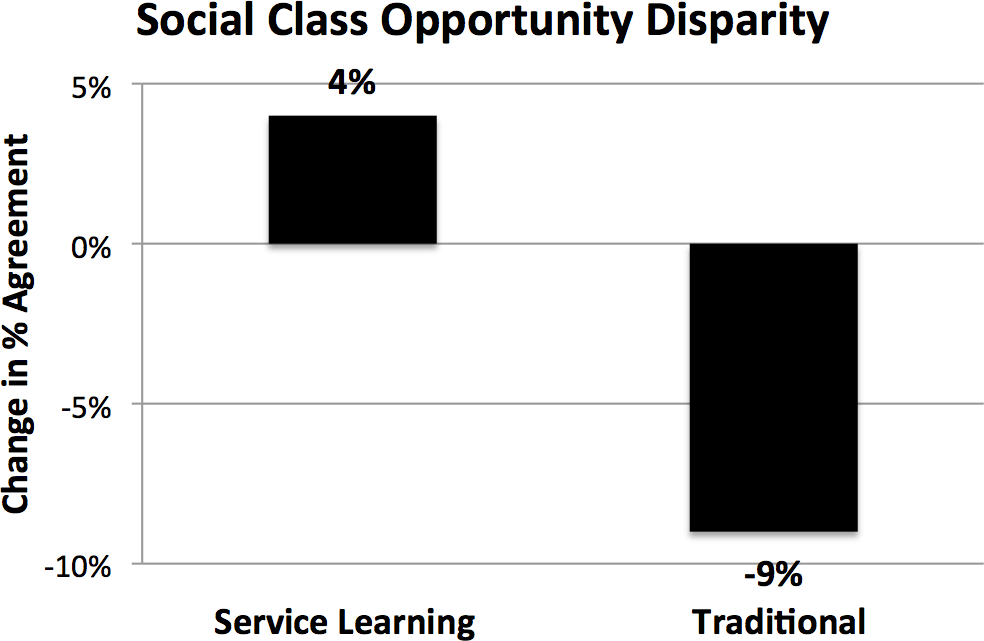

Figure 5 demonstrates an increase in agreement within the service- learning course and a decrease in agreement within the traditional course regarding the idea that students from poverty have fewer educational

|

opportunities than their middle-class peers. Fifty-seven out of the |

66 |

(86%) |

|

participants in the service-learning course agreed before, while 46 |

out |

of 51 |

|

(90%) agreed following the experience. Twenty-five out of the |

29 |

(86%) |

|

participants in the traditional course agreed before, while 23 out of agreed after the experience. |

30 |

(77%) |

Figure 5. Students from poverty have fewer educational opportunities.

Qualitative data indicated that after completing the course, students who struggled at the beginning to define diversity and service-learning could give at least a textbook definition of those terms (e.g., “The unique facets of individuals that contribute to the collective experiences, culture, abilities, and beliefs of a group”). Most students left the class with a clear understanding of the definition of service-learning and could use their own words in the definition (e.g., “Getting an invaluable learning experience through community service”). Several students, however, still held a one-sided view of service-learning (e.g., “Service learning is defined as projects to help better something or someone in the community”; “Getting involved in an organization in the community. Helping a cause you support”). Their comments tended to reveal a helping or charitable view of service-learning, rather than any learning on their part.

Most students agreed that diversity positively impacts the school experience of school-age children (e.g., “The more diverse a school experience is the more ready students will be for real life experiences”). One of the students who disagreed felt that kids don’t notice diversity. Another suggested that it either helps or hurts depending on who you are. Yet other students reported benefits but were vague in their descriptions (e.g., “They become more open”; “It creates a unique environment for everyone to learn in”).

Most students reported experiencing diversity at the university, albeit in “forced” situations (e.g., classes, professors, clubs) or in general, informal encounters. For example, one student responded, “At [the university] I have been in situations where I have had to tutor African and Asian students. Also I have had classes with people different from myself.”

Students reported that they encountered more diversity in their general education courses than in their teacher preparation programs. Again, this reflects the composition of the teaching and teacher candidate population.

Most students who reported having opportunities to experience diversity on campus also reported positive outcomes for themselves. One respondent indicated that the experiences “have caused me to have a newfound opinion about certain cultures I before just did not understand.”

Students reporting on their encounters with diversity at the university noted the following impacts and observations:

- “Gave me more respect for diversity”

- “Made me more open-minded”

- “Opened my eyes”

- “Gave me new respect for students with disabilities”

- “Taught me to appreciate everyone”

- “Taught me not to judge people”

- “Helped me think more about the topic”

- “Gave me a new perspective”

- “We’re not so different after all”

- “Changed my outlook on life”

- “Everyone can achieve”

- “We’re the same inside”

The data indicated that some students were either not open to self- examination or were correct in reporting their beliefs regarding changes to their personal views. Several students reported no impact since they felt they had always been open to diversity. When asked if their experiences with diversity at the university impacted their personal views, several students answered no: “I already know diversity is important”; “I’ve always been accepting of everyone. My parents made sure I was exposed to different people.”

When the students were asked to describe their experiences with diversity at the university, one individual wrote, “Many of the African American people have not gotten out of the way when walking opposite ways towards me even when the sidewalk is empty. Sometimes I have to get off the sidewalk.” The same student answered the follow-up question regarding how these experiences impacted his or her personal views: “Made me view African Americans as disrespectful.” Another student responded that there are “foreign people everywhere” and followed up with “It drives me crazy.” Clearly, different perspectives exist related to diversity.

The findings from this study have implications for change. The hiring of a vice president for multicultural affairs and community engagement at the study unversity signals a commitment to diversity and inclusion; however, in order for this person to effect change, faculty and students must also commit to being a part of that change. Universities might wish to highlight accomplisments such as national recognition for campus-wide accessibility in order to attract more diverse students. Professors can seek opportunities to invite more local leaders to speak as guest lecturers on the topic of diversity. Universities and faculty might identify opportunities to engage with the diverse surrounding community through partnerships, service-learning, and other activities. Service-learning experiences could also be included in more classes. In turn, these changes would potentially allow students more opportunities to interact and engage with others different from themselves. Wilson (2013) posed a challenge when he wrote, “Seemingly, as colleges and universities help prepare America’s future workforce and leaders, they have struggled to create effective multicultural campuses in which to do so.”

Furco (2002) spoke of providing public space for dialogue. These spaces offer safe places in which individuals can engage in often difficult dialogue. Universities need to provide such spaces. Heaggans and Polka (2009) stated:

Essential university-wide attitudinal changes are more likely to occur as the result of longer-term diversity educational programs where everyone benefits. Reforms should not assume that there is no need for diverse discussions just because there are no blatantly negative comments made about underrepresented groups or because people are openly nice to each other. (p. 24)

Universities should continue to strive to be open, safe forums for respectful dialogue.

This study led to several implications for university faculty. Just as students are asked to examine their beliefs, faculty also need to be willing to look inward. In a study conducted by Abes, Jackson, and Jones (2002), The Ohio State University faculty were asked what outcomes motivated them to use service- learning. The faculty identified five important factors including enhanced student learning of course content, the creation of university and community partnerships, the personal development of students, increased understanding by students of social problems, and the provision of useful service to the community. These attributes might be considered the heart of higher education’s purpose of helping students grow and learn in an authentic and meaningful context.

Finally, university classes can be models of inclusion, showing students how to teach in ways that foster respect for diversity and how to use diversity to benefit students in schools. Faculty members should be mindful and supportive of students, accepting them “where they are” and challenging them to examine their beliefs. Nito (2000) cautioned:

The decisions we make, no matter how neutral they may seem, have an impact on the lives and experiences of our students. This is true of the curriculum, books, and other materials we provide for them … what is excluded is often as telling as what is included. (p. 316)

In order to fully educate students, universities should continue to nudge them outside of their comfort zone, to provide opportunities to learn through community engagement, and to support students as they become engaged citizens. Bordelon and Phillips (2006) summed up the value of service-learning in this way: “The value of service-learning assumes that the learning environment extends from the classroom to the community, and that there are valuable resources fortifying students learning that cannot be obtained through participation in college alone” (p. 143).

The ability to understand and respect others is often considered vital to becoming a highly effective teacher of children. Our study suggests that many pre-service teachers lack that ability. Because our sample was small and limited to one campus, there is a need to continue this research on other campuses. However, program designers should consider service-learning as a means to increase the cultural competence of pre-service teachers. As Miller (2001) eloquently stated, “instead of pretending everyone is the same, we need to first accept the worries, the fears, the concerns and the prejudices—our own and those of our students—then take action” (p. 821).

References

Abes, E. S., Jackson, G., & Jones, S. R. (2002). Factors that motivate and deter faculty use of service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9, 5-17.

Banks, J. A., & McGee Banks, C. A. (Eds.). (2005). Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Jossey-Bass.

Barret, K. (2015). Welcome from the vice president for multicultural affairs and community engagement. Retrieved from: https://www.wright.edu/multicultural-affairs-and-community- engagement/about

Bordelon, T. D., & Phillips, I. (2005). Service-learning: What students have to say. Learning in Higher Education, 7(2), 143-153.

Brill, C. L. (1994). The effects of participation in service-learning on adolescents with disabilities. Journal of Adolescence, 17, 369-380.

Delpit, L. (1995). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York, NY: New York Press.

Furco, A. (1994). A conceptual framework for the institutionalization of youth service programs in primary and secondary education. Journal of Adolescence, 17(4), 395-409.

Furco, A., & Billig, S. (Eds.). (2002). Service-learning: The essence of the pedagogy (vol. 1). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Pub.

Garmon, M. A. (2004). Changing pre-service teachers’ attitudes/beliefs about diversity. What are the critical factors? Journal of Teacher Education, 55(3), 201-213.

Heaggans, R. C., & Polka, W. W. (2009). The diversity merry-go-round: Planning and working in concert to establish a culture of acceptance and respect in the university. Educational Planning, 18(2), 22-34.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1991). Beyond multicultural illiteracy. Journal of Negro Education, 60(2), 147-157.

Leiderman, S., Furco, A., Zapf, J., & Goss, M. (2003). Building partnerships with college campuses: Community perspectives. Washington, DC: The Council of Independent Colleges.

Miller, H. M. (2001). Teaching and learning about cultural diversity: Including the “included.” The Reading Teacher, 54(8), 820-821.

Nito, S. (2000). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (3rd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

Pohan, C. A., & Aguilar, T. A. (2001). Measuring educators’ beliefs about diversity in personal and professional contexts. American Educational Research Journal, 38(1), 159-182.

Rios, F., & Montecions, C. (1999). Advocating social justice and cultural affirmation. Equity & Excellence in Education, 32(3), 66-76.

Siwatu, K. O. (2007). Preservice teachers’ culturally responsive teaching self- efficacy and outcome expectancy beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 1086-1101.

Sleeter, C. E. (2001). Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: Research and the overwhelming presence of whiteness. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(2), 94-106

Su, Z. (1996). Why teach: Profiles and entry perspectives of minority students as becoming teachers. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 29(3), 117-133.

Su, Z. (1997). Teaching as a profession and as a career: Minority candidates’ perspectives. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13, 325-340.

Wilson, J. L. (2013). Emerging trend: The chief diversity officer phenomenon within higher education. The Journal of Negro Education, 82(4), 433-445.

Wright State University. (2015). Mission, vision, and values. Retrieved from: https://www.wright.edu/about/mission-vision-and-values

Author Biographies

Jason Fruth is an Assistant Professor and Intervention Specialist Program Director in Teacher Education at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Jason teaches courses in diversity and disability in the special education program and conducts research on the implementation of universal prevention strategies in the classroom and in the community.

Anna Lyon is an Associate Professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Wright State University. She teaches courses in assessment and literacy to undergraduate teacher candidates, and literacy courses in the graduate reading program. Her research interests include the impact of poverty on the education of children, school-university partnerships, and service- learning.

Anna Lyon is an Associate Professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Wright State University. She teaches courses in assessment and literacy to undergraduate teacher candidates, and literacy courses in the graduate reading program. Her research interests include the impact of poverty on the education of children, school-university partnerships, and service- learning.

Alan Avila-John is a graduate of the University of Dayton and is a prevention researcher in the chemical dependency program at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. His research interests include prevention strategies, outcomes of rehabilitation services, and service-learning for university students.

Alan Avila-John is a graduate of the University of Dayton and is a prevention researcher in the chemical dependency program at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. His research interests include prevention strategies, outcomes of rehabilitation services, and service-learning for university students.