Can a University’s Public Affairs Mission Move the Institution beyond Sustainability?

D. Alexander Wait

Missouri State University

Author Note

D. Alexander Wait, Professor, Department of Biology, Missouri State University.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to D. Alexander Wait, Professor, Missouri State University, 901 S National Avenue, Springfield, MO 65897. Phone: 417-836-5802. Email: AlexanderWait@MissouriState.edu.

Abstract

Institutions of higher learning spend considerable time linking their mission to every facet of the institution. More recently, considerable attention to sustainability has been a focus of almost every higher learning institution in the United States and many abroad. This paper is a case study exploring whether an institution with a strong, state-mandated mission in public affairs has infused sustainability into its mission or developed sustainability independent of its mission. Surveys of sustainability and public affairs curricula illustrate that curriculum based on the public affairs mission is dictated from the top, but that curriculum based on sustainability is a choice of individual faculty and academic departments. As a result, public affairs and sustainability are not linked at the curricular level. However, this case study illustrates administrative initiatives and student attitudes that indicate that a public affairs mission can move an institution “beyond sustainability.”

Keywords: public affairs, sustainability, administrative initiatives, student attitudes

Introduction

Many universities appear to be adhering to sustainability principles; however, how they address sustainability varies greatly, and integration with mission statements is far from complete (Dunpy et al., 2007). For example, institutional commitment to environmental sustainability can be discerned by whether its president or chancellor has signed the American College and Universities Climate Commitment. To date, 679 institutions have signed the commitment, and 533 have submitted climate action plans (ULSF, 2014). In addition, over 430 universities worldwide have signed the Tallories Declaration (University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, 2014). Within the Declaration, there is a commitment to graduate environmentally literate students who will go on to become ecologically responsible citizens (University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, 2014; see also Green, 2013). However, literature suggests that this goal is far from being realized (Bardaglio & Putman, 2009; Barth 2013; Brundiers & Weik, 2011; Brundiers & Weik, 2013; Brundiers et al., 2010; Winter & Cotton, 2012; Lukman et al., 2010). Institutional commitment to sustainability is also illustrated by the 837 higher education institutions that belong to the American Association of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE, 2014). In addition, 300 higher education institutions have gone through AASHE’s “Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System” or STARS. Within STARS, no institutions have received “platinum” status; however, 57 have achieved “gold,” 158 have achieved “silver,” 67 have achieved “bronze,” and 22 have achieved “reporter” status. Most of these institutions do not have sustainability as a mission, nor do they integrate sustainability into their mission explicitly (McFarlane & Ogazon, 2010). However, there are examples of institutions that have integrated sustainability into their existing mission very explicitly. There is also evidence that commitments to sustainability, whether specifically part of an institution’s mission or not, are not carried out equally across an institution (Green, 2013). For example, Green (2013) states that within economics at the three largest public universities in British Columbia, current introductory economics curriculum undermines the universities’ sustainability commitments.

It is well accepted that how a university focuses on sustainability will depend on the institution, its culture, priorities, mission, and its resources (Kerr et al., 2013; see also Barlett & Chase, 2004). There is also the understanding that sustaining an institutional mission is an evolving process (Weiss, 2009). Cusik (2008) provides an illustrative example of the University of Hawaii at Manoa “operationalizing” sustainability within their strong and evolving mission. Tang and Hussin (2013) provide an interesting example of advancing sustainability through a mission based on market needs and demands. However, even in institutions with clear missions in sustainability, and where the missions are based on environmental, social, and economic sustainability, only a small part of the educational pedagogy and actual curriculum addresses sustainability (McFarlane & Ogazon, 2011; Orr, 2004).

In 2012, the Journal of Public Affairs published a series of eight papers for a special issue entitled: “The Sustainability Challenge: Influencing the Change” (Millar et al., 2012). The editors compiled these papers to address the question: “The sustainability challenge: can public affairs influence the necessary change?” The editors of that special issue indicate that public affairs can address sustainability, in part because public affairs and sustainability are on parallel paths. However, since the definition of public affairs and sustainability are not clearly integrated the two areas are difficult to merge (Millar et al., 2012). Millar et al. (2012) (and references within) indicate that public affairs is reaching maturity and thus relatively definable by higher education institutions, while a definition of sustainability by higher education institutions is far from being determined. McFarlane and Ogazon (2011) see the problem of defining sustainability as the primary challenge to higher education institutions because there are no agreed upon definitions, which leads to fragmented understanding. Maser (2013) argues that sustainability can only be defined when educators, administrators, managers, decision makers, and societies as a whole recognize the well understood biophysical constraints’ of Earth systems to support human existence.

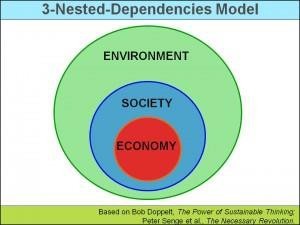

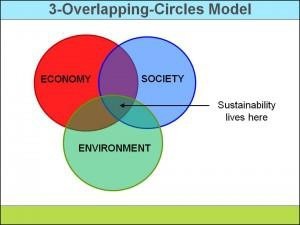

Definitions of sustainability and models that illustrate sustainability have been established formally starting since at least 1987 following the Brundtland report (Edwards, 2005). While definitions and models of sustainability have evolved over time, the core concepts of sustainability have not (Edwards, 2005). Three models that define sustainability have generally been assumed since 1987 (Edwards, 2005). Early in the primary and gray literature sustainability was conceptualized as three overlapping circles (Figure 1, left panel), with “sustainable development” occurring at the intersection of environment, economy, and society. This model inferred that the three areas can operate outside of the intersection, which is antithetical to the definition of sustainability (Edwards, 2005). A second model of sustainability was a “three-legged” stool, where the analogy was that if all three “legs” of sustainability were not being addressed equally then one leg is short and the “stool” (i.e., sustainability) would not be stable (Willard 2014). The most recent “model” (Figure 1, right panel) specifically recognizes the biophysical constraints of the environment (Maser 2013).

Figure 1: Two Models of sustainability (figures from Willard, 2014).

Figure panel on the left illustrates that sustainability is defined by the intersection of social equity (society), environmental integrity, and economic vitality. Figure panel on the right illustrates that environmental resources and processes limit and define social and economic sustainability (see Edwards, 2005, Maser 2013).

This paper examines whether an institution with a strong and state- mandated mission in public affairs has integrated sustainability into that mission. The goal of this paper is to build on the foundation of work published in 2012 in the Journal of Public Affairs linking public affairs and sustainability and to provide a case study of how an institution with a strong mission in public affairs has used the mission to explicitly address issues of sustainability and to suggest areas still in need of attention. The case study is not a critique, and it has heuristic value for the general understanding of the relationship between mission and sustainability, and specifically public affairs and sustainability. The focus is on integration through curriculum, although a history of public affairs initiatives and sustainability initiatives are also provided, as is a survey of student attitudes of sustainability.

Background and Methods Sustainability and Public Affairs

In 1995, the large midwestern public university that is the basis of this case study was granted a statewide mission in public affairs. The mission defined a primary way in which an education at the institution was different from that of other universities and one way by which students were educated to imagine the future. The mission was initially defined loosely and provided for a “value added” education. The mandate of the mission was as follows: “The University’s identity is distinguished by its statewide mission in public affairs, a campus wide commitment to foster competence and responsibility in a common vocation of citizenship”. By 2008 the mission had evolved to be defined by three pillars and goals:

- Ethical Leadership: Students will articulate their value systems, act ethically within the context of a democratic society and demonstrate engaged and principled leadership.

- Cultural Competence: Students will recognize and respect multiple perspectives and cultures.

- Community Engagement: Students will recognize the importance of contributing their knowledge and experiences to their own community and the broader society. Students will recognize the importance of scientific principles in the generation of sound public policy.

Searches on the university’s web pages reveal that participation in a national “Focus the Nation” event created widespread discussion of sustainability on campus in 2007. Two faculty members and a dozen students organized the events. The sustainability activities at the university associated with the Focus the Nation event were recognized and highlighted in the National Wildlife Federation’s “Campus Environment 2008: A National Report Card on Sustainability in Higher Education: Trends and New Developments in College and University Leadership, Academics and Operations” (National Wildlife Federation, 2008). In 2007, students formed their own sustainability organization. That student organization successfully lobbied for a Student Government committee on sustainability and for a $2-per-semester fee for sustainability projects, a fee passed and implemented in 2011. Also in 2011, the university joined AASHE and in 2012 was awarded “bronze” level in AASHE STARS (AASHE, 2014). The University constructed three buildings between 2011 and 2014 to meet LEED Silver certification. The president of the university also established a Sustainability Advisory committee in 2010. However, the university has not signed the Tallories Declaration or the American College and Universities Climate Commitment. In 2014 the university hired a full-time sustainability coordinator and defined sustainability as “…a commitment to environmental sustainability and stewardship. By working to create a cleaner environment through community service efforts, the application of earth-friendly technology and practices, research projects, and responsible development planning, we will strive to work for a better tomorrow. Through education and community outreach, we will provide students with the knowledge and skills to be environmentally responsible citizens and consider the global ramifications of their actions and the actions of others around them.”

Sustainability was explicitly linked with public affairs at the university in 2008- 2009 when the yearly public affairs theme was entitled “Sustainable Actions for a Sustainable Future.”

The latest long-range plan for the university (2011-2016) highlights the public affairs mission using the three pillars of public affairs as a guiding principle in all eight long-range planning goals. Sustainability is specifically mentioned in the goal to construct academic and auxiliary facilities consistent with the university’s commitment to sustainability. Sustainability activities at the university have received over $40,000 since 2008 from the university’s Office of Public Affairs to bring national sustainability leaders to campus, to underwrite staff, faculty, and student attendance at AASHE meetings, and to offer workshops to faculty to help them develop sustainability-based curricula. Finally, the university’s sustainability web page explicit states that “planning for sustainability [is] an evolving and iterative practice.”

Sustainability in Current Curriculum

I sent a survey to all faculty (n=694) at the university in 2010 that asked faculty to identify all their courses that were focused on or included some aspect of sustainability. The definitions used for the identification of courses came from ASSHE (2014): “Sustainability-focused courses concentrate on the concept of sustainability, including its social, economic, and environmental dimensions, or examine an issue or topic using sustainability as a lens. Sustainability-related courses incorporate sustainability as a distinct course component or module, or concentrate on a single sustainability principle of issue.”

I developed and presented the survey language to all college deans for comment and approval. The survey was sent to department heads for comment and approval who, in turn, disseminated the survey to their faculty. Approximately four weeks later, department heads were to send a list of all sustainability-related or sustainability-focused classes. The survey was also posted on the Provost’s web site and noted in the weekly Provost’s Communiqué so that it was widely available to all faculty. Reporting was for one academic year based on total number of undergraduate courses offered in the fall 2010 (n=1,194). In 2012, a call for courses to be included in a minor in sustainability was emailed to all deans, department heads, and faculty. A committee of 12 faculty then reviewed courses and determined which courses met the definition of “sustainability-focused,” for the minor.

Student Attitudes on Sustainability

Because the minor has not yet gone through the formal curricular process, a faculty committee of 10 developed a survey to be sent to all freshman and sophomores enrolled at the university in spring 2013 to assess the interest in a minor in sustainability. The committee sent the survey to 6,561 students, and the response rate was approximately 4%. The students were asked a series of 10 questions (see Appendix, Table 1). In addition, there was a text box where students could write comments. Only 27 students wrote comments.

Public Affairs in Current Curriculum

I attained an internal public affairs document from the university to assess public affairs curriculum over time; the document was an internal committee report where the committee was charged with assessing public affairs in the curriculum. Data were also provided by the registrar. One science department was also surveyed by a faculty member for the number of courses that have public affairs components.

Results

Sustainability and Public Affairs

Only relatively informal connections between public affairs and sustainability have come to fruition at the institution. The inclusion of sustainability in one part of one goal (out of eight goals) of the current long-range plan indicates that sustainability has been included in the university mission. Extensive research produced no formal documents stating links between public affairs and sustainability except for the one statement quoted in the Background and Methods section above. However, once the administration connected sustainability at some levels to a public affairs mission, it began funding sustainability projects and chose sustainability as its public affairs theme for the 2008-2009 academic year.

Sustainability in Current Curriculum

The general curricular survey to all faculty in 2010 indicated that 8.7% (105 out of 1194) of courses at the university contained some aspect of sustainability (“sustainability-related”) and 2.3% (27 out of 1194) of courses were “sustainability-focused.” However, these courses are found in only 30% of the departments on campus (15 out of 51). The Department of Geology, Geography, and Planning produced the most sustainability-related or –focused courses. In requests to all faculty for courses to be considered for a minor in sustainability, the number of courses that met the definition of sustainability-focused, as reviewed by a committee of 12 faculty, increased to 3.3% from those reported in 2010, and two additional departments were represented. In both cases, all six colleges at the university had at least one department submit a course for a proposed minor in sustainability.

Student Attitudes on Sustainability

The survey of freshman and sophomore students on sustainability and sustainability curriculum conducted in 2013 illustrates that a sustainability minor would be relevant to students at the university (see Appendix, Table 1). For example, the majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that “the concept of sustainability is very important to society today.” However, only about 50% of the respondents think more than a basic understanding of sustainability is needed for their major. Overall, survey results indicated that most students agree that sustainability is important, but when asked about sustainability in their curriculum, they tend to be neutral or disagree more than agree. While very few of the respondents wrote comments, one comment may reveal that students are cognizant of measures related to sustainability on campus (e.g., recycling, no trays in dining halls, hydration stations, water and energy conservation messages in residential housing), but they are not offered curriculum that provides reasons for sustainability broadly defined by environment, equity, and economics.

Public Affairs in Current Curriculum

Since the public affairs mission was established the university has indicated on their web site that: “The Universities Public Affairs mission is implemented not only in the public space of the classroom, but also outside the University through internships, field experiences, government service, volunteer programs, service learning programs, and a variety of other forms of community engagement and outreach.”

As a general education requirement, all students have to complete one public affairs course. That course was “PLS 101 American Democracy and Citizenship.” The course catalog description is as follows: “This course familiarizes students with the institutions and constitutional framework of the United States and Missouri. The course emphasis is on the values, rights, and responsibilities that shape the public decision making of active and informed citizens and influence contemporary public affairs in a democratic society.”

In 2014, a new general education curriculum was approved and the “public affairs” requirement is now one to three courses that touch on public affairs in every major. Therefore, the one course (PLS 101) for all students will no longer be required, but all 51 departments at the university have to have at least one course that emphasizes public affairs as defined by ethical leadership, cultural competence, and/or community engagement. In addition, a general introduction to university life course required for all students is required to provide an introduction to the public affairs mission. The available public affairs courses are currently being determined by each department. One science department requires a single public affairs course and lists 13 courses that meet the requirement. In comparison, the list of courses in that department that are sustainability focused is three. Those three classes are also on the list of public affairs courses.

One recent (2013) effort by the university’s Public Affairs Office to capture the number of courses on campus that are “public affairs intensive” resulted in 28 departments submitting a list of courses. In total, 211 courses were identified as public affairs intensive —approximately 18% of all undergraduate courses. Interestingly, on that list the same science department detailed above proposed six courses.

Discussion

This case study examined the link between a public affairs mission and sustainability curriculum and concludes that the link is so far quite weak. This may be because public affairs curriculum appears to directed from the offices of the president and provost, while the sustainability curriculum is being proposed by a small group of faculty that are using the public affairs mission as a guide. All departments are required to designate courses as public affairs focused, and the courses have to be approved by the faculty senate. Sustainability courses are viewed more narrowly than public affairs as measured by the number of course offered. Sustainability-focused courses at the university have to address all three pillars of sustainability (Figure 1), while public affairs courses only have to specifically address one pillar of public affairs. Farnsworth (2010) concluded that when a university implements sustainability curriculum from the top, it links it with mission. That is how public affairs curriculum is implemented at the university examined but not how sustainability curriculum is being implemented. Nonetheless, many of the courses proposed for the sustainability minor overlap with public affairs courses. In addition, the faculty committee developing the minor proposed that the minor be housed in the Office of Public Affairs within the Provost’s office, and the Provost’s office is supporting that model. If the sustainability minor is approved there will be a clear link between sustainability and the Public Affairs mission.

The curricular data and history of public affairs indicates that the university has embraced and integrated its mission of public affairs into the fabric of the university and has also embraced sustainability and integrated it into some of the fabric of the university. Select faculty conducted the survey of student attitudes on sustainability for the purpose of arguing that the university should establish a minor in sustainability. Therefore, the survey does not inform any potential overlap of sustainability and public affairs. However, the student survey provides evidence that students at the university are generally aware of, and believe that, sustainability is important in their education. A survey that links public affairs and sustainability is needed, especially since every student is required to take two to four public affairs courses to graduate. A survey could assess student awareness of public affairs and establish whether students can make a connection between public affairs and sustainability.

Moving beyond sustainability seems to be a new direction for sustainability in academia. This issue of the eJournal of Public Affairs is evidence, as is the 2012 special issue of Journal of Public Affairs. In that special issue, Robinson (2012) developed an argument for linking public affairs and sustainability around the fact that science now posits that the Earth is in a new geological epoch, termed the “Anthropocene.” Robinson introduces the question of the Anthropocene defining sustainability and public affairs by discussing an article in the Economist that sought to link the Anthropocene to economic vitality (2011). However, the Economist article did not grasp the magnitude of the Anthropocene, which illustrates how human society and economies are and will be constrained by environmental resources and processes (Robinson, 2012). A recent article in the New Yorker (2013) and a book by Elizabeth Kolbert (2014) describe the process of how an epoch gets determined in lay terms and clearly states how social and economic sustainability are constrained by the environment. Robinson sums up the challenge of linking public affairs and sustainability by stating that “although physical conditions have changed, human socio-economic endeavors still proceed as in the past, on the basis of increasing obsolete assumptions about natural systems and resources.” Maser (2013) describes the sustainability challenge, writing, “Science deals with an understanding of biophysical relationships; society asks questions about human values.” Figure 1 (right panel) is consistent with those two views of sustainability and provides the framework for integration of public affairs and sustainability.

Sherman (2010) suggests that sustainability education has to move beyond champions of the movement to providing more coverage of the topic, a suggestion also applicable to public affairs. That is, to move beyond sustainability in public affairs, sustainability would have to be more than an “add on” to the public affairs curriculum. For example, Sherman cites word association exercises on sustainability with undergraduates and faculty, and 90 percent identify sustainability with recycling or some other proposed practice which misses the broad important aspects of sustainability (see Figure 1). All incoming freshman at the midwestern public university examined in this paper encounter the three pillars of public affairs, and the broad aspects of sustainability could be incorporated into the curriculum along with public affairs.

Outside of academia, moving beyond sustainability is also a current issue. For example, McDonough and Braungat’s recent book, The Upcycle: Beyond Sustainability – Designing for Abundance (2013) argues for one way to look beyond sustainability, although the authors do not explicitly recognize biophysical constraints of the biosphere. An economic model for moving beyond sustainability closer to understanding biophysical constraints is provided by the “Interface Model” as described by Anderson (1999) and Anderson and White (2011).

In conclusion, this large midwest public university may not meet the benchmarks for being a leader in sustainability among higher education institutions as set out by McFarlane and Ogazon (2011), Eisen and Barlett (2006) or Lukman et al., (2010), but it is a leader in public affairs and is also very aware of sustainability benchmarks. For example, the university is striving to reach Silver level in AASHE STARS in 2015. The case study illustrated that the development of public affairs curriculum has been kept separate from development of sustainability curriculum, and this may be because the university has not yet made the connection between sustainability and its mission. Eisen and Barlett (2006) articulated over eight years ago that “the broader academic mission across departments and programs is often slower to connect with sustainability efforts,” and this needs to occur for any institution to move beyond sustainability.

References

Anderson, R. C. & White, R. (2011). Business lessons from a radical industrialist. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Anderson, R. C. (1999). Mid-course correction: Toward a sustainable enterprise: the interface model. Atlanta, GA: Peregrinzilla Press.

Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. (2014, March). Retrieved from http://www.aashe.org/.

Bardaglio, P., & Putman, A. (2009). Boldly sustainable: Hope and opportunity for higher education in the age of climate change. Washington, DC: National Association of College and University Business Officers.

Barlett, P.F & Chase, G.W. (2004). Sustainability on Campus: Stories and Strategies for Change. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Barth, M. (2013). Many roads lead to sustainability: a process-oriented analysis of change in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14(2), 160-175.

Brundiers, K., Wiek, A., & Redman, C.L. (2010). Emerald article: Real-world learning opportunities in sustainability: from classroom into the real world. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 11(4), 308-324.

Brundiers, K., & Wiek, A. (2011). Educating students in real-world sustainability research: Vision and implementation. Innovative Higher Education, 36, 107-124.

Brundiers, K., & Wiek, A. (2013). Do we teach what we preach? An international comparison of problem- and project-based learning courses in sustainability. Sustainability, 5, 1725-1746.

Cusick, J. (2008). Operational sustainability education at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 99(3), 246-256.

Dunphy, D., Griffiths, A. & Benn, S. (2007). Organizational change for corporate sustainability 2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Edwards, A.R. (2005). The sustainability revolution: Portrait of a paradigm shift. Gabriola Island, B.C., Canada: New Society Publishers.

Eisen, A., & Barlett, P. (2006). The piedmont project: Fostering faculty development toward sustainability. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(1), 25-36.

Farnsworth, J.S. (2010). When university presidents become tree huggers: A report from the field. Climate Neutral Campus Report (2nd ed.). Kyoto Publishing. Vancouver, B.C. Canada. 50-53

Green, L. (2013). Teaching (un)sustainability? University sustainability commitments and student experiences of introductory economics. Ecological Economics, 94, 135-142

Glover, A., Peters, C., & Haslett, S.K. (2011). Education for sustainable development and global citizenship: An evaluation of the STAUCH auditing tool. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 12(2), 125-144.

Kerr, K.G., & Hart-Steffes, J. S. (2012). Sustainability, student affairs, and students. New Directions for Student Services, 137, 7-17.

Kolbert, E. (2014). The sixth extinction: An unnatural history. New York, N.Y. Henry Holt and Company, LLC.Kolbert, E. (2013). Annals of extinction: The lost world. The New Yorker, December 23, 2013 Issue. 48-57.

Koppl, P. (2012). Green lobbying: Is sustainability more than a new frame for old-style lobbying? A consultant’s personal point of view. Journal of Public Affairs, 12(3), 177-180.

Lukman, R., Krajnc, D., & Glavič, P. (2010). University ranking using research, educational and environmental indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18, 619-628.

Maser, C. (2013). Decision making for a sustainable environment: a systematic approach. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

McDonough, W. (2013). The Upcycle: Beyond sustainability-designing for abundance. New York. N.Y North Point Press.

McFarlane, D.A., & Ogazon, A.G. (2011). The challenges of sustainability education. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 3(3), 81-107.

Millar, C., Gitsham, M., & Mahon, J. (2012). The sustainability challenge: can public affairs influence the necessary change? Journal of Public Affairs, 12(3), 171-176.

National Wildlife Federation. Campus Environment 2008: A National Report Card on Sustainability in Higher Education: Trends and New Developments in College and University Leadership, Academics and Operations. (2008, August) Retrieved from http://www.nwf.org/pdf/Reports/CampusReport82008Finallowres.pdf.

Orr, D. W. (2004). Earth in mind: on education, environment, and the human perspective. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Robinson, N.A. (2012). Beyond sustainability: Environmental management for the Anthropocene Epoch. Journal of Public Affairs, 12(3), 181-194.

Sekerka, L.E., & Stimel, D. (2012). Environmental sustainability decision- making: clearing a path to change. Journal of Public Affairs, 12(3), 195- 205.

Sherman, D.J. (2010). Uncovering sustainability in the curriculum: integrating sustainability in higher education curriculum requires powerful shits in pedagogical thinking. Climate Neutral Campus Report (2nd ed.). Vancouver, B.C, Canada: Koyto Publishing. 70-73.

Tang, S.F., & Hussin, S. (2013). Advancing sustainability in private higher education through quality assurance: A study of two Malaysian private universities. Asian Social Science, 9(11), 270-279.

ULSF | University Leaders for a Sustainable Future. (2014, March). Retrieved from http://www.ulsf.org/.

Weiss, C.S. (2009). Sustaining institutional mission through “Pilgrimage”. Liberal Education, 95(3), 56-60.

Willard, Bob (2012, October ). The three sustainability models: Ways to explain sustainable societies. Retrieved from https://www.2degreesnetwork.com/groups/2degrees- community/resources/three-sustainability-models-ways-explain- sustainable-societies/.

Winter, J., & Cotton, D. (2012). Making the hidden curriculum visible: Sustainability literacy in higher education. Environmental Education Research, 18(6), 783-796.

Wright, T., & Horst, N. (2013). Exploring the ambiguity: what faculty leaders really think of sustainability in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14(2), 209-227.

Appendix

Table 1: Survey of freshmen and sophomore students about sustainability curriculum. Results (mean ± standard deviation (SD)); n=259 to 219 because some questions were not answered by all participants) of a survey of all freshman and sophomores on sustainability attitudes and need for sustainability focused curriculum at a large Midwestern state university. Student answers were categorized as 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5= strongly agree. One student comment* is included that best represents an awareness of sustainability on the campus and illustrates that sustainability is not included in curriculum.

|

Question |

Mean ± SD |

|

The concept of sustainability is very important to society today |

4.27±0.96 |

|

For the majors I am interested in, I won’t need much more than a very basic understanding of the concept of sustainability |

2.85±1.24 |

|

Understanding the impact of human activity on the natural environment should be a top priority in universities today |

3.87±1.04 |

|

We don’t need to worry too much about sustainable development of our cities |

1.78±0.93 |

|

My future career will depend heavily on understanding issues of sustainability |

3.21±1.20 |

|

It will be important to incorporate issues of sustainability into my personal life |

3.99±0.93 |

|

Sustainability matters the most to farmers |

3.38±1.32 |

|

Every undergraduate at this university should be well-versed in problems of sustainability |

3.85±0.99 |

|

I would be interested in taking a minor related to sustainability |

3.04±1.33 |

|

Learning more about sustainability is very important to my choice of major |

3.13±1.30 |

*The student’s comment is as follows: “I have been very impressed with the measures the university is already taking concerning sustainability because I come from an area where sustainability was not a concern. I definitely think it can do more though. I feel like most of the information I have received about sustainability is being told what we should be doing without really explaining why. So yes, I think that making learning about sustainability some kind of an education requirement would be beneficial.”

Author Biography

D. Alexander Wait is a Professor in the Department of Biology at Missouri State University (MSU). His research examines plant/animal interactions and plant community responses to fire, carbon dioxide, temperature, precipitation, nitrogen, seabird activity and carbon nanotubes. He has done field-based research and teaching across the U.S. and in Mexico and Ecuador. He teaches Plant Ecology, Conservation Biology and an honors seminar on Sustainability. He was Provost Fellow for Public Affairs in 2009 at MSU, and was a founding member and past president of Ozarks New Energy, Inc. He holds a Ph.D. in Biology from Syracuse University.