Addressing Political Inequality by Restoring the Civic Mission of Higher Education

Abraham Goldberg

University of South Carolina Upstate

Author Note

Abraham Goldberg, Department of History, Political Science, Philosophy, and American Studies, Office of Service-Learning and Community Engagement, University of South Carolina Upstate.

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Abraham Goldberg, Associate Professor of Political Science, Director of the Office of Service-Learning and Community Engagement, University of South Carolina Upstate, 800 University Way, CLC 202, Spartanburg, SC 29303. Phone: 864-503-5670. E-mail: agoldberg@uscupstate.edu

Abstract

This article argues that colleges and universities serving diverse, historically marginalized students can combat political inequality by serving a civic mission. Social science research has shown that socioeconomic status is a strong predictor of political participation, meaning political leaders are chosen by and hearing from a sample of the population that is wealthier, older, and better educated than everyone else. Preparing students from underrepresented demographic groups for active and enlightened democratic engagement will bring important new voices and unique perspectives to the political arena. The author’s current institution serves a high percentage of lower-income and first-generation students. Its civic mission embeds political learning across the curriculum, fosters service-learning opportunities, and encourages open discussions about contemporary issues and problems. The author also argues that classroom and campus environments that value the personal well-being of students facilitate political learning and engagement. Ultimately, colleges and universities serving underrepresented populations can address political inequality by adequately preparing students for a life of active democratic participation.

Keywords: civic engagement, political learning, diversity

Self-preserving political actors have an electoral incentive to respond favorably to the interests of people who participate in elections. Conversely, there is less reason to champion interests of those who do not (or cannot) return the favor with votes. Indeed, voter participation rates are not distributed evenly across all segments of society, raising important questions about the state of representative democracy in America. People who are younger, poorer, and less educated vote at far lower rates than all other groups. Barely 20% of those who never graduated from high school voted in the 2014 midterm election, compared to over 50% of college graduates. In the same election, approximately 30% of people in families earning less than $20,000 per year voted, compared to 55% of people in families earning more than $100,000. Less than 25% of 18 to 34 year olds voted, compared to about 60% of people over the age of 64 (File, 2015). Within such statistics, there is an important distinction that must be highlighted: American elections more closely reflect the voice of the privileged than the voice of the people.

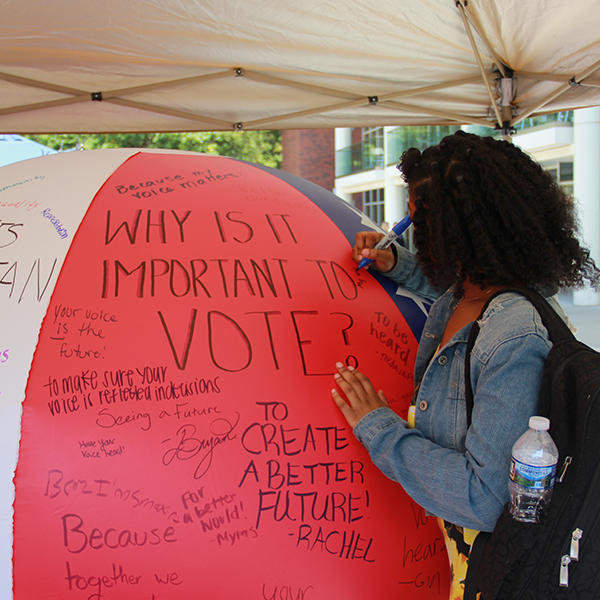

I argue that colleges and universities must assume a prominent position on the frontline in the battle to curb political inequality, especially those institutions that serve underrepresented students. Preparing students from historically marginalized groups to be active and enlightened participants in the democratic process during their undergraduate experience will ultimately diversify the electorate and incentivize political leaders to account for a more representative sample of the American population. A college degree alone, however, will not adequately prepare students for meaningful political and civic engagement. Democratic participation requires a deep sense of political empowerment and relevant skills in order to be an effective agent of influence—a message that must be emphasized throughout the undergraduate experience, regardless of students’ chosen majors.

My current institution serves a diverse population, with a high percentage of lower-income, first-generation students. Three mechanisms used to prepare students for active citizenship are embedding political learning across the curriculum, encouraging political discourse in the classroom, and promoting service-learning opportunities. However, learning to be civically and politically engaged can be daunting, even intimidating, especially for underrepresented college students. Therefore, the institution fosters a supportive campus environment in which faculty and staff universally care deeply about the personal well-being of students. Not only does this represent a moral responsibility, but it facilitates academic achievement and encourages students to engage the uncomfortable, controversial issues that accompany political learning. The campus’s approach to political learning is at least partially validated by the student voter turn-out rate, which exceeded expectations in the 2012 presidential election. When colleges and universities serving historically marginalized populations restore the civic purpose of higher education and prepare students for robust democratic engagement, political inequality and the dominance of the elite-driven political order can begin to fade.

Restoring the Civic Mission

College attendance and completion alone will not inspire political engagement. Students must learn how to be active and effective participants in the public sphere while enrolled. A quick review of elite universities’ mission statements reveals lofty phrases—such as “developing responsible citizen leaders,” “serve the community,” and “promote the public welfare”—that demonstrate foundational commitments to civic and democratic education. However, a growing chorus of academic leaders have made serious accusations about whether the civic mission of higher education has been devalued.

In A Crucible Moment (2012), the National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement argued that “a robust approach to civic learning is provided to only a minority of students, limiting higher education’s potential civic impact. Too few postsecondary institutions offer programs that prepare students to engage questions Americans face as a global democratic power.” (p. 2). Similarly, in his keynote address at the Campus Compact Presidents’ Leadership Colloquium, Alexander Astin (2004) argued that institutions of higher education are not achieving their civic missions. Instead, the prevailing wisdom is that colleges and universities exist to keep America technologically and scientifically competitive in a globalized society, while providing personal economic benefits to those who graduate. Peter Levine (2007) argued that many people attend college as a means to achieve future financial stability, and college administrators respond by highlighting marketable skills and building elite, restricted networks that link recent graduates to previous ones for internship and job opportunities.

Outside pressure to restore the civic mission has intensified, however. Over 360 colleges and universities currently hold the Carnegie Foundation’s elective Community Engaged Classification, reserved for institutions that provide evidence of a mission and practices that support reciprocal partnerships between campuses and their broader communities (New England Resource Center, n.d.). Additionally, the President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll was created to recognize campuses that position students to address issues within their community while earning an undergraduate degree (Corporation for National and Community Service, n.d.), and Civic Nation developed the All-In Campus Democracy Challenge, encouraging colleges and universities to develop strategies aimed at increasing student voter participation (Civic Nation, 2016).

Although such initiatives are promising and exciting, more can be done to recognize and incentivize campuses for promoting civic and political learning. The prominent U.S. News and World Report (Morse & Brooks, 2015) oddly omits civic education—and many other metrics concerning a quality learning experience— from the criteria used to rank institutions in its annual Best Colleges rankings. Academic reputation, student selectivity, graduation rate, and faculty compensation are all weighted heavily, despite foundational commitments to civic education at most institutions. Political learning should be central to the college experience and acknowledged accordingly.

Beyond Voting

Institutions must not slip into the faulty logic that higher student voting rates alone signal achievement of the civic mission. Robust political engagement is not limited to voting in pre-organized, government-sanctioned elections. Students who rely on voting as the sole mechanism to influence change should prepare themselves for disappointment. Elections are predictable. In my state, the same political party has won every presidential election since 1980, and my congressional district has been led by the same party for the past 23 years. The consistency and predictability of election results in my state is not an anomaly but, increasingly, an American norm. Bill Bishop (2008) chronicled the evolving geopolitical landscape and found that more Americans than ever are living in counties dominated by one of the major political parties.

Voting in elections also does not adequately reflect the true political beliefs of voters. Sidney Verba and his colleagues (1995) argued that votes “communicate little information about the concerns and priorities of the voter,” while “many other kinds of participation arrive with specific issue concerns attached” (p. 13). For all of its benefits, a two-party system forces voters to simplify, rank, and categorize issues—not an easy or even reasonable charge for a young person attempting to navigate a pluralistic society. Some have even questioned whether choosing to vote at all is a rational decision, given the time commitment relative to the potential individual benefit.

Voting in free elections is central to sustaining our democracy but does not, by itself, satisfy the demand for broad political engagement. Students must understand that the most significant societal changes in the U.S. have resulted from political activities including marching, boycotting, partnering, protesting, lobbying, coalition building, compromising, convincing, and fighting. Engaging in these activities requires inspiration, empowerment, and skills, all of which can be acquired during a formal education. In their Guardian of Democracy report, Jonathan Gould and colleagues (2011) maintained that civic education enhances the knowledge and skills necessary for effective and informed democratic engagement. Further, civic education promotes a sense of civic duty and empowerment that yields greater and more effective political participation. Colleges and universities have a responsibility to ensure that students appreciate all of the ways citizens can influence societal outcomes, teach skills that will enhance their effectiveness, and inspire them to value the importance of political activity.

Robust Political Learning for a Diverse Student Body

At my institution, about one third of students are the first in their family to attend college. Roughly one third are classified as students of color. About three out of four students receive need-based financial aid (U.S. News and World Report, 2016). Over half of the 2016 freshman class received a Pell Grant, and about 28% of students who completed a FASFA came from families earning less than $25,000 per year.

The institution serves LBGTQ students, some of whom confront the unthinkable challenge of being rejected by their families because of who they are. The campus serves students with strongly held religious beliefs whose churches are central to their lives, others who are atheists, and others trying to reconcile their upbringing with new exposure to a pluralistic community. The campus also serves students returning home from fighting in wars and others returning to school after seeing their children graduate from college.

Many of the institution’s students live complicated, challenging lives. Most work countless hours in menial part-time jobs. Some are raising their own children.

Some have parents who do not value higher education and are unable or unwilling to provide support when students experience the natural challenges of earning a college degree. While the students are incredibly resilient, college careers can end prematurely when work schedules conflict with class schedules or when constructive feedback on assignments is interpreted in ways that make students feel like they do not belong.

A bevy of research has indicated that students at my institution are less likely to vote and engage in other forms of political activity than students at “higher ranked” colleges or those serving a wealthier student demographic. Political participation is predicted by socioeconomic status (see Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Further, young people are far more likely to vote in their first eligible election if their parents were voters and civically engaged in their communities (Beck & Jennings, 1982). Such evidence lends itself to a political system that favors the privileged. However, my institution—as well as others like mine—have an opportunity to weaken political inequality if it succeeds in preparing students for effective democratic engagement.

My institution serves its civic mission by embedding political learning across the curriculum, supporting service-learning, and incorporating political discourse in the classroom. All students are required to complete a first-year writing composition program with a curriculum designed to prepare and inspire students to become engaged citizens. The first course incorporates writing assignments reflecting upon famous essays by authors including Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, and Paul Krugman. The student-created response papers act as launching pads for open class discussions about the historical and contemporary political issues raised in the reading assignments. The second course in the sequence challenges students to identify and conduct research on local community issues. Further, students propose solutions to public problems and identify leaders and organizations within their community empowered to implement changes. This is all accomplished in a class designed initially to simply teach writing skills! The program introduces first-year students to the notion that political engagement is important and valued at the institution, and that confronting public problems is part of the undergraduate experience.

In addition, a first-year reading program focuses on present-day topics of popular interest. Recent common books have included a collection of gay and lesbian memoirs that coincide with Supreme Court decisions on gay marriage, a novel focusing on African-American experience in the South, a book on economic uncertainty in America and the challenges faced by those trying to survive by working minimum wage jobs, and a biography that raises questions about bioethics and the effect of gender and race on medical care (USC Upstate, 2016). The book selection is accompanied by class discussions and writing assignments in the composition courses, as well as a “University 101” course designed to acclimate new students to the institution. Students attend co-curricular events led by faculty from across the institution, community members with relevant expertise or insight, and often the authors themselves.

Like many institutions, mine offers American National Government and American history courses (though these are not required for all students and should be) to give students a baseline understanding of government structure and powers, civil rights, and civil liberties, and the role of non-governmental influences on decision making. The courses also help students appreciate the context under which our political system was created, and how it has changed over time. Civic knowledge is a necessary prerequisite for effective political engagement, and many students come to college with a limited understanding of our political system (Gould, 2011). American history and government courses can stimulate political activity; however, political learning is not limited to specific classes. The institution’s first-year composition and reading programs—as well as other courses that address political themes—are critical to preparing students for active citizenship.

My institution also has an administrative unit charged with building opportunities for faculty to incorporate relevant, discipline-specific community service into courses. Service-learning empowers students to employ newly developed skills to address public issues in partnership with community organizations. For instance, a microbiology class spoke to kindergarteners about germs and taught proper handwashing techniques. Students in a criminal justice course served as academic tutors for inmates a local detention center preparing for a high school equivalency exam. A Spanish class translated important documents for local nonprofit organizations serving the quickly expanding Hispanic community. Students in a sociology of aging course partnered with assisted living centers to provide company to residents, and they conducted interviews in order to create memoirs for the residents. Students in the nursing program created a Teen Health Expo and invited middle schoolers to learn about healthy living habits. In each of these examples, the service experiences connected directly to course objectives.

Students who participate in service-learning courses have heightened political awareness, enhanced sense of relating to people from different cultures, and greater confidence in their ability to make contributions to their communities through service (Simons & Cleary, 2006). One student who participated in a course that partnered with a local art museum commented: “When I think about service- learning classes, I’ll look back at this experience and I’ll remember how it changed me. It’s made me better at my research and it has made me more comfortable in asking questions.” (Farr Shanesy, 2016). So many of the institution’s students come from families that are not heavily embedded in community affairs, and service- learning connects them to local leaders in their disciplines who often later serve as internship or job supervisors. It also provides opportunities for students to understand and address local public issues.

Service-learning is further embedded into the campus culture by being valued in hiring decisions, the promotion and tenure process, and other faculty awards. It is also prominent in the campus’s external communications. A “Service- Learning Spotlight” initiative features service-learning courses on the institution’s homepage. New stories are added every two weeks, doubling as press releases to local media outlets. This outreach ensures that the institution is positioned to be a valuable resource for the community it serves.

Another important tool for preparing students for active political engagement is to incorporate discussions about political issues in the classroom. My comfort with decentralizing the classroom for my students has evolved since joining the faculty seven years ago. I originally viewed my role strictly as a lecturer, charged with imparting wisdom as the “sage on the stage.” Perhaps this was a preferred method for an inexperienced teacher hiding insecurities about losing control of the classroom or not having “right” answers all the time.

Fortunately, I learned a valuable lesson early in my career when an unscripted discussion emerged from a lecture. The lesson was that students actually had important things to say! Therefore, I accepted the responsibility of giving them a platform. I started reserving occasional “seminar-style discussion” days on my class schedule, devoted exclusively to giving students the opportunity to engage each other around issues related to the course content. My classes became more interesting, more important, and more fun. They also became more enriching given the exposure students had to each other’s varying perspectives.

Incorporating political discussions in the classroom offers an important training ground for students being challenged to become actively engaged in democracy. Should convicted felons ever retain voting rights? What can be done about mass-incarceration? How would the political system change if voting became a requirement for everyone? Should governments use public money to invest in sports arenas when people are living on the street? Should low-income housing be concentrated in pre-determined sections of cities? Should all third-grade teachers be required to use an identical curriculum? Do the benefits of neighborhood gentrification outweigh the costs? Are people in your community generally trustworthy? My students engage questions and topics like these that are uncomfortable to address—and off limits in many living rooms and dinner tables.

Incorporating political discourse in the classroom can also be deeply personal. At the Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement meeting, Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg (2016) coined the “silent civics curriculum” to describe the narrative that each student develops through his or her own personal encounters with civil society. The silent civics curriculum is formed by individual life experiences—positive and otherwise—and provides powerful insights for discussions on political issues.

The diversity of students at my institution—and the silent civics curriculum they experienced—is an asset to political discourse, and the challenges many of them confront in their lives provide authenticity to class discussion. Meaningful political discourse overcomes dominant narratives about polarized society. Learning from different perspectives is emphasized rather than “defeating” the opposition. Students learn to respect opposing positions and celebrate the magical moments when consensus is reached despite differing political, religious, and social beliefs. My students could teach certain political leaders some very important lessons about respect and compromise.

Safe but Uncomfortable

A safe environment is paramount for political learning—not comfortable but safe. The classroom must be treated as a quasi-sacred space allowing students the opportunity to explore their perspectives without fear of retribution or intimidation. Instructors are responsible for creating an environment of mutual respect, and typically the students reinforce it. Speaking freely about uncomfortable political matters with a diverse group is refreshing and inspiring in an academic environment.

A safe classroom environment is reinforced by a culture of caring and respect across my campus. The faculty and staff care very deeply about the personal well-being of students. How can students succeed personally or academically if no one on campus cares about their lives? How can a student take risks and explore new, potentially controversial ideas without the comfort of a foundation? Such concern for student well-being is symbolized by the Career Closet, operated within Academic Affairs, and the RUOK (i.e., Are You OK?) campaign, operated within Student Affairs. The Career Closet accepts donated suits and business attire from faculty and staff which students can access prior to engaging the job market as they approach graduation. Interviewing for jobs and internships is daunting enough as it is, and this program reduces anxiety while ensuring that graduating seniors maintain a professional appearance.

The RUOK campaign places RUOK stickers, which include contact information for the Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs, on building entrances and other prominent locations across campus. It opens an important door for students needing access to services including counseling, housing, and financial aid. Both the Career Closet and the RUOK stickers are physical manifestations of a campus culture of caring. Faculty and staff are committed to (and strategic about) ensuring that students—despite the challenging life circumstances many of them face—are positioned to succeed.

The students confront the typical challenges of needing help finding a social group and feeling overwhelmed by academic requirements. However, some situations are direr. Several dorm rooms are kept vacant for homeless students, and a food pantry is stocked by faculty and staff. I have seen the campus’s most civically engaged students access the food pantry. My institution educates students and prepares them for active political engagement, but it also saves their lives.

Conclusion

E. E. Schattschneider (1960) famously argued that “the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with a strong upper-class accent” (p. 35). Over a half-century later, a signature feature of the American political system remains the wide economic and social disparities between those who actively participate and those who do not. Those who shape policies and those who do not. Those who are empowered and those who are not. Those who feel that political leaders are accountable to them and those who do not. The political and social inequality puzzle has not been solved, and some argue it is more difficult than ever to climb out of disadvantaged life circumstances (Putnam, 2015).

Colleges and universities serving diverse, historically marginalized students are positioned to address political inequality. Young people from underrepresented demographic groups are less likely to vote and participate in other forms of political activity than others. However, if institutions of higher education serve their civic mission by preparing these students for active political and civic engagement, then new voices and unique perspectives will be included in decision-making processes.

Getting students to voting booths is a worthy and important endeavor. The Institute for Democracy and Higher Education’s National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement offers a free report to campuses interested in learning the registration and voting rates of their students, stratified by age, class, and major (Tufts University, 2016). Colleges and universities should participate in the study and publish their data for the campus community to reflect upon. It is a starting point—and perhaps instigator—for campus discussions about preparing students for a life of political participation. However, institutions of higher education must also think more broadly about democratic engagement than simply voting.

My campus serves its civic mission by embedding political learning in courses across the curriculum. The English composition faculty view their role as encouraging political participation as much as those teaching political science. Students are encouraged to participate in service-learning, which gives them an opportunity to address local issues connected to their fields of study using newly developed skills. This is incredibly empowering. At my institution, students also learn how to engage in civil and productive dialogue on political and social issues during their undergraduate experience. These are not the only methods of serving the civic mission, and surely the institution does more than what is described in this article. I encourage all readers to consider what their campuses are currently doing to prepare students for sustained political engagement—and what they could be doing differently.

Political learning is challenging and uncomfortable, especially for those confronting difficult life circumstances. Discussions about poverty, racism, and prejudice can, moreover, be deeply personal to students. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the entire university community to foster a culture that cares about the well- being of others, regardless of political, social, and religious beliefs. Campuses are communities and should be treated as such.

Ultimately, democratic renewal begins when higher education becomes accessible to everyone, when institutions recognize the challenges that many students confront in their lives, and when the civic mission is prioritized. Colleges and universities serving underrepresented populations have the ability and the civic duty to address political inequality by preparing all students for enlightened democratic engagement.

References

All In Campus Democracy Challenge. (n.d.). How it works. Retrieved from http://www.allinchallenge.org/#how-it-works

Astin, A. (2004, October). Exercising leadership to promote the civic mission of higher education. Speech presented at Campus Compact’s Presidents’ Leadership Colloquium, Carmel, CA.

Beck, P., & Jennings, M. (1982). Pathways to participation. American Political Science Review, 76(1), 94-108.

Bishop, B. (2008). The big sort: Why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Corporation for National and Community Service. (n.d.). President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll. Retrieved from http://www.nationalservice.gov/special-initiatives/honor-roll

Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 422 432.

Farr Shanesy, C. (2016, March 29). Learning outside four walls: Service-learning offers students an opportunity to work, learn in the community. Retrieved from http://news.uscupstate.edu/2016/03/learning-outside-four-walls- service-learning-offers-students-an-opportunity-to-work-learn-in-the- community

File, T. (2015). Who votes? Congressional elections and the American electorate: 1978-2014. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/de mo/p20-577.pdf

Gould, J., Hall Jamieson, K., Levine, P., McConnell, T., and Smith, D. B. (2011).

Guardian of democracy: The civic mission of schools. Philadelphia: Leonore Annenberg Institute for Civics of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania and the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools.

Greenstone, M., Looney, A., Patashnik, J., & Yu, M. (2013). Thirteen economic facts about social mobility and the role of education. Washington, DC: The Hamilton Project.

Kawashima-Ginsberg, K. (2016, June). Connecting the dots: Why we need to care about civic learning on and off college campuses. Speech presented at the Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement meeting, Indianapolis, IN.

Levine, P. (2007). The future of democracy: Developing the next generation of American citizens. Medford, MA: Tufts University Press.

Morse, R., & Brooks, E. (2015, September). Best colleges ranking criteria and weights. U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved from: http://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/ranking-criteria- and-weights

National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement. (2012). A Crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

New England Resource Center for Higher Education. (n.d.). Carnegie Community Engaged Classification. Retrieved from http://nerche.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=341& Itemid=92#CECdesc

Putnam, R. D. (2015). Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Schattschneider, E.E. (1960). Semi-sovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Simons, L., & Cleary, B. (2006). The influence of service learning on students’ personal and social development. College Teaching, 54(4), 307 – 319.

Tufts University. (2016). NSLVE frequently asked questions. Retrieved from http://activecitizen.tufts.edu/nslve-faq

University of South Carolina-Upstate. (n.d.). PREFACE: The USC Upstate first- year reading and writing experience. Retrieved from https://www.uscupstate.edu/academics/arts_sciences/languages_literature/ preface.aspx?id=16412

U.S. News and World Report. (2016). University of South Carolina-Upstate. Retrieved from http://colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best- colleges/usc-upstate-6951/paying

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Author Biography

Abraham Goldberg is an Associate Professor of Political Science and serves as Director of Service – Learning and Community Engagement at the University of South Carolina Upstate. He authored the South Carolina Civic Health Index and has published numerous academic articles about the relationship between the urban built environment, social connectivity, and resident quality of life. Abe regularly supervises undergraduate research projects and teaches courses in urban planning and policy, public administration, civic engagement and American politics. He earned his doctorate from West Virginia University and resides in Greenville, South Carolina with his wife and two children.

Abraham Goldberg is an Associate Professor of Political Science and serves as Director of Service – Learning and Community Engagement at the University of South Carolina Upstate. He authored the South Carolina Civic Health Index and has published numerous academic articles about the relationship between the urban built environment, social connectivity, and resident quality of life. Abe regularly supervises undergraduate research projects and teaches courses in urban planning and policy, public administration, civic engagement and American politics. He earned his doctorate from West Virginia University and resides in Greenville, South Carolina with his wife and two children.