Civil Dialogue for the Twenty-First Century: Two Models for Promoting Thoughtful Dialogue Around Current Issues on a College Campus

Emma Humphries

Shelby Taylor

H. Anne Weiss

University of Florida

Author Note

Emma Humphries, Assistant in Citizenship, Bob Graham Center for Public Service, University of Florida: 220 Pugh Hall, P.O. Box 112030, Gainesville, FL 32611. Ph. 352.846.1575, Fax 352.846.1576. ekhumphries@ufl.edu; Shelby Taylor, Digital/Communications Director, Bob Graham Center for Public Service, University of Florida; H. Anne Weiss, Graduate Assistant in Civic Engagement, Center for Service and Learning, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

Abstract

This manuscript describes two models for promoting civil dialogue around important social and political issues on a college campus—Democracy Plaza at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) and The Civil Debate Wall at the University of Florida (UF)— and examines the differing types of expression fostered by each platform, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of each platform. By doing so, it offers important insights for institutions of higher learning that seek to promote not just civil dialogue, but also a culture of civility and engagement, on their respective campuses. Whether armed with a budget of one million dollars or just one thousand dollars, campuses can and should create spaces for meaningful dialogue surrounding important issues.

Introduction

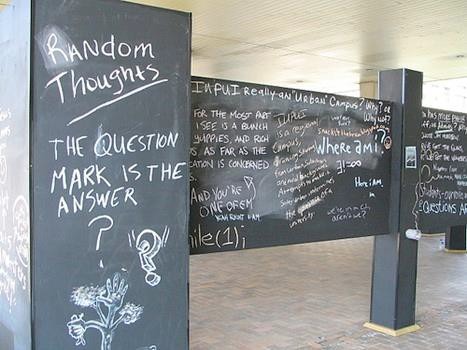

The purpose of this manuscript is to describe two models for promoting civil dialogue around important social and political issues on a college campus— Democracy Plaza at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) and The Civil Debate Wall at the University of Florida (UF)—and to compare the two in terms of their platform, the types of expression they foster, and their general strengths and weaknesses. Democracy Plaza at IUPUI is a physical space (see Appendix A) on which students discuss current issues on large chalkboards. The Civil Debate Wall at UF is both a physical space and a virtual space (See Appendices B – D), employing digital and social technologies for students to respond to provocative questions.

We begin by offering a conceptual framework that captures the necessity of civil dialogue in a democratic republic and justifies the investment in spaces that promote such dialogue on college campuses, in either traditional or digital form. We then explore each platform—first Democracy Plaza followed by The Civil Debate Wall—by providing detailed information about their respective development, goals, and user experiences. Next we offer a comparative case study analysis of the two platforms by analyzing the types of expression and user experiences we have observed as well as detailing the strengths and weaknesses of each platform. We end by discussing the implications for current and future efforts to promote civil dialogue on college campuses.

Conceptual Framework

An informed citizenry that is willing and able to discuss important socio- political issues and events in a civil manner is an oft-neglected bedrock of democratic republicanism (Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, 2011). Indeed, civil discourse and taking seriously the perspectives of others lay at the heart of democratic society. They also represent the best hope for achieving compromise, consensus, and, ultimately, responsible public policy in a country as diverse as the United States of America and an international community as vast and segmented as the one we know today (Shea, Kovacs, Brod, Janocsko, Lacombe & Shafranek, 2010). Sadly, warns David Mathews, president of the Kettering Foundation, what ought to be thoughtful deliberation about public issues has been replaced with incivility and hyperpolarization (London, 2010).

Fortunately, college campuses provide the perfect laboratories for developing and practicing the democratic skills of perspective taking and civil dialogue, and as institutions of higher learning, they have a responsibility to promote both. That is, the 1998 Amendments to the Higher Education Act of 1965 require all academic institutions to provide voter registration materials to students and to foster and encourage a sense of civic responsibility and engagement among students. This obligation has recently received increased attention. Earlier this year, The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012) issued a call to action entitled A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future. It included five “Key Recommendations for Higher Education”, the third of which is to “Make civic literacy a core expectation for all students” through the deployment of “powerful civic pedagogies such as intergroup and deliberative dialogue” (p. 32).

This recommendation is supported by studies that demonstrate the positive impact of such pedagogies (Association for the Study of Higher Education, 2006; Gurin, Nagda, & Sorensen, 2011; Harriger, & McMillan, 2007; Schoem, & Hurtado, 2001) as well as others that show that college students actually want more meaningful opportunities to discuss and address public issues (Kiesa, Orlowski, Levine, Both, Kirby, Lopez, & Marcelo, 2007). It also serves as a natural extension of the types of civic pedagogies that are encouraged during K-12 schooling. For example, the 2011 Civic Mission of Schools Report (Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools) urges schools to offer civic learning experiences that encourage and increase young people‘s civic engagement. Specifically, it enumerates Six Promising Approaches to Civic Education, the second of which advises schools to “[i]ncorporate discussion of current, local, national, and international issues and events in the classroom, particularly those that young people view as important to their lives” (pp. 6–7).

Of course, important questions remain regarding the actual spaces and opportunities for intergroup and deliberative dialogue. This paper operates from the assumption that both traditional and digital spaces hold tremendous promise for encouraging and facilitating civil discussion on a college campus. Given the proliferation of digital technologies and Internet spaces for civic and educational purposes, especially among young people, it makes sense to utilize both when resources allow for it (Cohen & Kahne, 2012; Kahne, Middaugh, & Evans, 2009; Keeter, Zukin, Andolina, & Jenkins, 2002; van Hamel, 2011). Still, the familiar and low-risk appeal of chalkboards, whiteboards, and other low-tech platforms can, as this manuscript will demonstrate, encourage robust and meaningful discussions as well. Below is one such example.

Democracy Plaza at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis

Democracy Plaza (DP) at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) was created to provide the IUPUI community with opportunities to share diverse thoughts and perspectives surrounding social and political issues. The project was started in the summer of 2004 when a group of undergraduate students, faculty, and staff came together to address the benefits and drawbacks of a physical structure, outside of the walls of traditional learning spaces, that would provide a free and common place where open discussion, written expression, and various forms of everyday political talk could take place in the spirit of fair play and the exchange of ideas.1

The physical structure of DP has changed three times since it was unveiled in 2004, but it has always been located in the heart of the IUPUI campus: outside and underneath the breezeway of the business school. The original structure included only two large, mobile chalkboards, which were chosen for reasons related to accessibility, engagement, cost, and sustainability. However, students’ reaction to the two chalkboards (and their non-permanent status) indicated that something larger and more conducive for hosting events would make for a better design. By the next summer, DP grew to include eight chalkboards, which were placed in a “V” shape and by the fall of 2007, DP grew to include 22 chalkboards and two community bulletin boards. These boards, now in their final design, came together in the shape of a “U” and form a permanent landmark on the IUPUI campus where students can engage in everyday political talk, either on the chalkboards or through one of many events hosted at DP each year.

As the physical structure was in the process of development, so too was a student organization of the same name, which will be referred to as Democracy Plaza Student Organization (DPSO).2 The DPSO is in charge of maintaining DP and hosting programs around the mission of the organization: “[…] to support the development of well-informed and engaged students through critical thinking and civil discourse on political ideas and issues” (“Democracy Plaza”, n.d.) Since its inception in 2004, the DPSO has comprised a small group of students known as “Civic Engagement Leaders” (CELs) who receive a modest scholarship as compensation for the time and effort they spend on planning events and maintaining DP.

1 The impetuses for DP were the 2000 and 2004 United States presidential elections. Following these elections, many felt that there should be a designated space on campus where students can talk about social, economic, political, environmental, or other difficult and controversial issues. 2 DP is purely student driven. One part-time and one full-time staff member advise the students. These staff members, students, and the organizational entity of DP are funded through a partnership between the IUPUI Center for Service and Learning and Office of Student Involvement. The American Democracy Project Committee at IUPUI (ADP @ IUPUI) is an informal advisory board for both the staff and students involved in maintaining and supervising DP.

Maintenance of DP requires multiple activities, the most important of which is cleaning and posting new questions on the chalkboards. Every week, each CEL submits three questions that pertain to a current event or a political idea or issue. These questions are compiled and edited for length and language (e.g., the spelling out of acronyms, no slang, and general grammar considerations) by a designated CEL who then gives the final list to two or three CELs who are assigned to clean the chalkboards. Each chalkboard is cleaned every week with one new question posted on each of the 22 chalkboards. The questions then appear on the chalkboards for one week before they are cleaned and new questions are posed.

It is important to note that the questions could stay on the chalkboards for longer than one week, but DPSO members have found that one week affords plenty of time for people to respond to the questions and potentially come back and view others’ comments. Additionally, DPSO members report that the chalkboards invariably become quite full and “messy” by the end of the one-week period. As another important consideration, the climate of Indianapolis, coupled with the fact that DP is located on a college campus, means that weather and the academic calendar have a significant impact on the timeframe during which questions are posted. Typically, new questions appear every week between mid-August and mid- November during the fall semesters and from mid-March until the last week of classes (typically the first week of May) during the spring semesters. Questions are not placed on the boards during the summer months.

Another important task of maintaining DP is being prepared to deal with hateful or threatening speech when it occurs on the chalkboards. According to its mission statement, IUPUI holds “a strong commitment to diversity” and IUPUI’s Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion “is constantly endeavoring to improve our culture and make certain the environment is conducive to learning and growth for all people.” Nonetheless, it is important to be prepared for the possibility that certain members from within or outside of the University (IUPUI is located in the heart of Indiana’s capital city, Indianapolis, and is open to visitors) may not share in its commitment to providing a safe and welcoming educational environment for all people. From DP’s beginning in 2004 through the present, the issue of hateful or threatening speech has been brought up on an annual basis, either by a concerned member of the IUPUI community or by the CELs who clean the chalkboards.

In anticipation of this issue, a group of students, faculty, and staff at IUPUI convened before DP’s construction in order to decide how to handle hateful or threatening speech. The consensus was that hate speech should be tolerated in the name of free expression of ideas. From this meeting, a list of guidelines (See Figure 1) was created, with the largest guideline tackling the issue of hateful or threatening speech. These guidelines, as well as the actions taken by the DPSO when hateful or threatening speech appears, align with upholding the civil discourse aspect of the DPSO mission statement. Although the DPSO will allow such speech to remain on the boards, it chooses to address hateful or threatening speech through events at which the community can come together to discuss it in a civil manner.3

3 One example comes from the spring of 2012 when someone wrote, “Obama must die” on one of the chalkboards. CELs saw the comment and approached their advisor. It was decided that they would contact a professor from the IUPUI School of Law, who confirmed that the message met the criteria for threatening speech. In response, DPSO convened a “Free Speech” event. The previously consulted law professor spoke at the event, which brought in over 60 students to discuss the boundaries of free speech. In the end, another DP participant (not a member of DPSO) revised the original statement to read, “Obama loves ice cream.” No further action was deemed necessary. Click here to view a short video from a different event that was held at DP.

Democracy Plaza Guidelines on Speech & Displays

The rules and regulations for the Democracy Plaza are designed to provide an opportunity for the community to express their opinions on subjects affecting them as democratic citizens and members of the campus community in an atmosphere of fair play and exchange of ideas.

- The most important rule is that the “spirit of fair play” prevails.

- Please check the weekly calendar on the Democracy Board for previously scheduled events, forums, discussions, panels, et cetera.

- If you would like to reserve the Democracy Plaza for a class, discussion, meeting, et cetera please contact the Campus & Community Life Office and they will make every attempt to accommodate your request.

- We need to be mindful of the diversity that exists at IUPUI and prepare for the possibility of hate speech. In order to address this we have held several discussions with key administrators, the IUPUI Police, and extended invitations to students, faculty, and staff that may be affected by such messages in the future. It seems we have come-up with a basic question that would need to be asked and answered. Is the speech and or message a threat or is it hateful?

- If the speech and or message is a threat, the IUPUI Police will be notified and take the lead role in investigating, dealing with, and forwarding these occurrences to the proper authorities and the threat will be removed.

- If the speech or message is hateful then we plan to use it as an opportunity to educate. Should such message or speech arise we plan to hold a discussion panel to talk about the case in point in a non-hostile, but academic environment. We will plan for the worse, and hope for the best.

Figure 1. Democracy Plaza Guidelines on Speech Display

The nature of DP allows for multiple levels and various types of interaction. First, interacting on the boards is completely anonymous; the only way someone would know if a particular individual wrote on the chalkboards or what that particular individual wrote on them would be if he or she saw that individual while writing. Second, the very nature of a chalkboard (and therefore, the medium of chalk) allows for comments to be written, erased, drawn over, or crossed out, and therefore, the interactions on the boards are not limited to simply writing a response.

That said, the expression that occurs is limited by the fact that one needs to be on campus in order to participate. Third and finally, as already mentioned, the chalkboards fill up with comments by or before the end of each week, and many people may not find room to write if the topic addressed in the question is a “hot button” issue. These varieties of interactions give DP its unique nature, and continue to be one of the main reasons it has been replicated both nationally and internationally as a way to engage students in civil dialogue around important social and political issues.4 They also made for an interesting comparative case study with the Civil Debate Wall at the University of Florida, which is described below.

The Civil Debate Wall at the University of Florida

In 2010, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation awarded a three-year, three million dollar grant to the Bob Graham Center for Public Service at UF5 to support its pioneering approach to prepare UF students to be informed, skilled, and engaged citizens. There are five distinct categories of activities in the grant:

- To create the Knight Effective Citizenship Fellowship, the intent of which is to assemble a group of visiting scholars to collaborate with scholars at UF and other universities, as well as experts and advocates for participatory citizenship from other sectors.

- To develop an interactive online citizenship course to be tested at UF and brought to national audiences.

- To build and implement an electronic “Civil Debate Wall” to provide a forum for students and citizens in Gainesville to engage in civil and public discussion on current issues.

- To utilize and study new social media tools to understand how these technologies can develop informed, skilled, and engaged citizens.

- To evaluate experiential programs and study civic participation behavior of students and alumni.

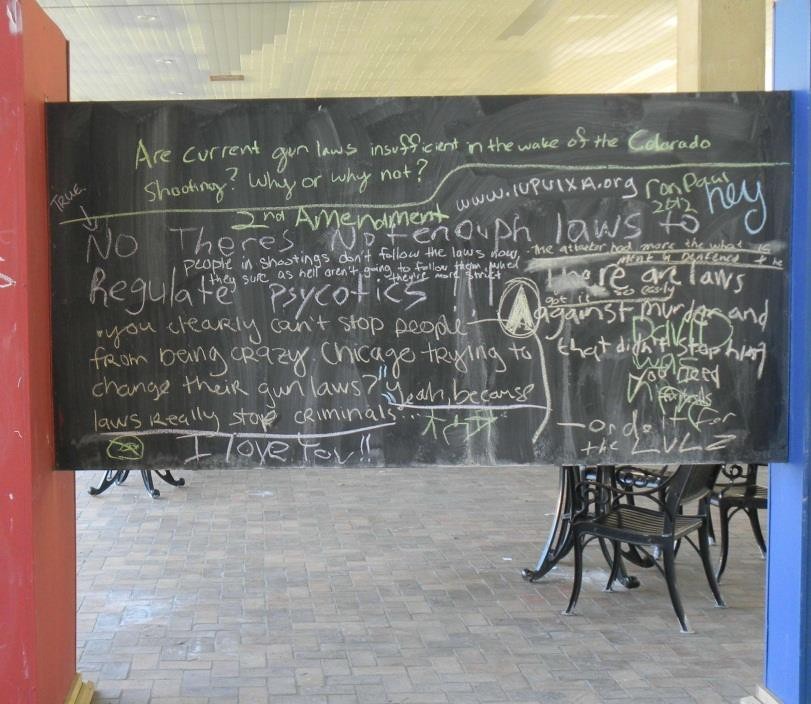

4 For example, after the shooting in an Aurora, Colorado movie theater, a DP chalkboard asked, “Are current gun laws insufficient in the wake of the Colorado shooting? Why or Why not?” The responses on this board ranged from comments alluding to the shooter’s Second Amendment rights to “No. There’s not enough laws to regulate psychotics or guns.” Some referenced other cities trying to regulate where guns can be carried while others simply wrote “Yes” or “No” or drew an arrow pointing to another’s response with a “True” statement (See Appendix E).

5 Located in Gainesville in north-central Florida, UF is a major, public, land grant research university. In addition to being the state’s oldest and most comprehensive university, UF is among the nation’s most prestigious public universities and a member of the American Association of Universities. Total enrollment is 49,589 of which 32,598 are undergraduate students and 16,991 are graduate and professional students. UF has a student to faculty ratio of 20 to one and a 43 percent admittance rate.

For the third category, the Graham Center embarked upon a novel experiment in bridging the physical and virtual worlds of civic discourse. The result was The Civil Debate Wall, or as it is popularly referred to on campus, The Wall. The Wall’s physical component is a series of interconnected touch-screen devices at UF’s Pugh Hall, home of the Graham Center, that allow users to share ideas and solutions to some of the most pressing public policy questions.6 The Wall also operates virtually in synchronized real-time through its own website: www.civildebatewall.com. This remote interaction allows users to post original opinions or join an existing debate from anywhere in the world.

The primary goal of The Wall is simple: to promote civil dialogue around important current issues. In this way, The Wall seeks to encourage users to be informed, to be civil, and to be engaged. There are also a series of ancillary goals for The Wall:

- To connect students from diverse populations, disciplines, and political ideologies in the discussion of issues that affect everyone.

- To facilitate consensus building over divisive and controversial public policy issues.

- To inspire an interest in public policy and public service.

With these goals in mind, the Graham Center worked closely with students over a one-year period to develop this new media tool to capture the imagination of a generation raised with the Internet, smartphones, sophisticated games, and continually evolving social media.

While the goals of The Wall are rather traditional and academic, the experience of using The Wall is quite innovative. Every couple of weeks, a new question is posted on The Wall. These questions, drafted and selected by UF students, tend to center around current news trends and therefore entice users to discuss “hot topics” that they have probably been hearing a lot about in the news, at coffee shops, and on social media sites.7

6 Click here to view a short video of physical version of The Wall.

7 For example, just days after President Obama voiced his support for same-sex marriage, The Wall asked, “Was the president’s recent declaration in support of same-sex marriage simply a calculated political gesture?” Many students were confidently ready to respond to the question, given that they had already been tracking the issue. Others might have been inclined to research the issue so that they could make an informed contribution to the unfolding discussion on The Wall.

Upon deciding to engage The Wall, users have two entry options. The first option is to respond directly to the question. All questions are limited to a “Yes” or “No” response and the user begins by tapping one of those two boxes. The second option is to respond directly to another user who has already answered the question. Either way, the next step is for the user to type in a response that answers the question, “What would you say to convince others of your opinion?” Like Twitter, these responses are limited to 140 characters, thereby promoting clear and succinct justifications, rather than long-winded editorials or rants. Once the user has completed his or her response, The Wall takes his or her picture. Therefore, The Wall is not anonymous and tends to discourage the kind of vitriolic discussion that is oftentimes seen in online discussion threads. Lastly, The Wall gives the user the option to enter his or her smartphone number, which will allow him or her to follow the debate remotely. This feature works by sending a text message to the user’s phone every time another user responds to his or her opinion.

Unlike other social media tools, The Wall is more than a sounding board. It is also a tool for studying dialogue. By simply tapping a “View Debate Stats” icon, users can take advantage of a system of integrated analytics to explore discussion data. For example, referring to the question regarding President Obama’s declaration in support of same-sex marriage, a user could see that 100 people participated in the debate, that 65 users registered a direct response to the question, and that of those 65 users, 48% responded “Yes” and 52% responded “No”. A user could also tell that user Will posted the most popular response (calculated by the amount of “Likes” received) by choosing “No” and then writing, “I believe the President has always been for it. I think it was a calculated political move to refrain from expressing his view until now.”

Perhaps most importantly, because The Wall’s technology can sift through key words found in user posts and tabulate them in dynamic data visualizations that illustrate areas of agreement (See Appendix F), a user could see that across user posts on both sides of the issue, the words “choice” and “rights” were commonly found. This is a powerful finding, demonstrating likelihood that many individuals, regardless of the way in which they viewed the President’s declaration, believe that this issue is fundamentally about choice and rights. This has the potential to facilitate consensus building by allowing users and other interested individuals or groups to then use that information to move toward potential solutions.

The Wall remains, in many ways, an experiment. With each new question, something new is learned about the nature of discussion, the power of question phrasing, the nuances of a particular issue, and the ways in which young people are enticed to participate in the discussion of important public policy issues. For this reason, it makes for an interesting comparative case study with DP at IUPUI in order to uncover the ways in which a physical and virtual space matches up to an exclusively physically space, and, in doing so, reach a deeper understanding of what it means to foster civil dialogue on a college campus.

Method

In order to compare the types of expression and user experiences we have observed at DP and on The Wall and to identify the respective strengths and weaknesses of each, we conducted a comparative case study analysis of the two platforms. Case study is a special kind of qualitative research that investigates a contemporary phenomenon (Hatch, 2002; Merriam, 1988; Yin, 1994). The comparative variation is applied when the researcher(s) seek to compare different phenomena that may share some features or characteristics, within specified boundaries (Druckman, 2005). In the context of this study, the boundaries were specified as user expression and experience in order to focus the analysis on the phenomena of engaging with DP or The Wall.

Comparing Democracy Plaza and The Wall

In this section, we explore the differing platforms and types of expression and offer our critique of each space. Despite very similar goals, both platforms foster unique forms of participation that make each a tremendous example of civil dialogue on a college campus. Some of the differences are obvious—or example, using chalk versus using a touch-screen panel, a computer, or a mobile device— while other examples were more difficult to uncover but hold greater meaning for our quest to understand the best way to facilitate civility and awareness among college students, be they traditional or non-traditional, residential or commuter. Differences aside, it is our position that both platforms hold great promise for the future of civil dialogue in academic spaces.

The Platforms

Many of the differences across the two platforms are immediately apparent. DP comprises 22 chalkboards and two community bulletin boards, which come together in a “U” shape. The Wall consists of five touch-screen panels and a synchronous website and mobile website. DP can host many different questions at one time by placing one question on each of the 22 chalkboards every week during the academic calendar. The Wall can only post one question at any given time. DP allows for much variability of response. Participants can write new comments— either stand-alone or in response to another participant’s comment—or they can erase, draw over, or cross out existing comments. They can also draw pictures, draw lines connecting comments, or edit the question itself. The Wall limits variability of response. Participants may respond directly to the question or respond to another participant’s response. Either way, he or she must designate a “Yes” or “No” response to the question and is only afforded 140 characters to defend his or her stance. Participants also have the option to “Like” comments made by other participants. The last major difference between the two platforms is access to the space: DP requires students to physically visit in order to participate while The Wall can be accessed remotely from a computer or mobile device. Additionally, DP is located outside and is therefore subject to the weather elements of Indianapolis, thereby limiting students from cleaning and posting new questions on the boards for four months out of the calendar year.

Types of Expression

As mentioned in the previous section, an important comparison between these two platforms is the type of expression, or talk, they promote and how that talk is moderated or facilitated in order to create awareness and engagement around some of today’s most pressing social and political issues and events (e.g., same-sex marriage, immigration, health care, tuition costs, campus elections). As Figure 2 illustrates, the displays of expression between the platforms have some interesting similarities and differences. It is important to note that these types of expression are limited to what can be observed and that other types of expressions, or talk, are likely present during or after engagement with either platform. Overall, these lists

are examples of the types of expression we have observed. The degree to which these spaces foster deep or robust expression falls outside the scope of this manuscript but will certainly be the focus of future research.

Debate Humor Drawings Symbols Questions

Advertisements Voting

Decision-making

Stories

Opinion sharing Information sharing

Debate Humor Questions Voting

Decision-making Opinion sharing

Debate Humor Questions

Voting Gestures

Facial expressions Decision-making Opinion sharing

Figure 2. Comparing expression across the two platforms

Nonetheless, it is safe to assume that, through these various types of expression, both platforms demonstrate engagement—engagement with the topic(s) raised in a given prompt; engagement with other respondents (that is, the back-and-forth of asynchronous dialogue or deliberation); engagement with student, civic, or private organizations; and/or engagement with information through opinion forming and sharing. In a word, expression is the essence of engagement for both DP and The Wall. This befits the role of institutions of higher learning to “become a more vigorous partner in the search for answers to our most pressing social, civic, economic, and moral problems…” (Boyer, 1996, p. 13) and supports a view of civic engagement as an all-encompassing concept of expressing oneself, or learning to express oneself, in order to build consensus and find creative solutions.

While both platforms support the goal of their respective organizations to promote civil expression, the ways in which they do so are vastly different. DP is considered a free speech space. That is, the student leaders who maintain and oversee the chalkboards have decided to not engage with the chalkboards anytime between cleaning and writing new questions, and they rely on individuals to monitor their own participation on the chalkboards. To be certain, this aspect of the DP experiment can be both challenging and uplifting. However, as stated by the DP guidelines above, should hateful or threatening expression occur, it becomes a “teachable moment” and is used as a way to educate the public through a campus- wide event in which individuals can meet to talk about the expression and decide if any further action is warranted.

The Bob Graham Center takes a more active role in ensuring that The Wall remains a civil space, primarily by removing opportunities for anonymity. Users who visit the physical version of The Wall on campus have their picture taken, which tends to encourage good behavior (although users can always step out of the camera frame or hold something over their faces). Remote users must log in before registering their opinion. Another strategy, which is a deliberate feature of the software design, allows users to flag inappropriate opinions, which then bounces a message to an administrator at the Bob Graham Center who can decide to remove the speech or let it stand. However, this is a rare occurrence because the software contains a database of offensive speech and will not allow users to post an explicitly inappropriate comment in the first place.

Strengths and weakness

DP allows for all forms of expression and, through this space, individuals can police themselves and facilitate the kind of talk that promotes critical-thinking, understanding, and civility. Additionally, DP is entirely run by students and can be easily replicated on another campus, which has already occurred. Unfortunately, engagement with DP is contingent upon an individual physically visiting DP. For that reason, the possibility of expanding the platform to an online space is currently being considered. Such an expansion would likely encourage and facilitate greater engagement in the important act of civil dialogue.

The Wall is sleek. It is catchy, it is clean, and it is unlike any other space for civil dialogue. It is also virtually accessible; one need not physically visit The Wall to engage with The Wall. Nonetheless, there are technological confines to The Wall. Its slick, clean design is a double-edged sword. While attractive and enticing, the linearity of the dialogue it fosters leaves little room for tangential comments, illustrative drawings, or big-picture representations. To be sure, much is gained and much is lost when pursuing a purely digital platform for civil dialogue.

Implications

First impressions matter. This is especially true when trying to generate excitement around a new campus project. At first glance, DP is easy. All one needs is a piece of chalk and an opinion to participate. At first glance, The Wall is enticing. Even the most distracted passerby cannot help but notice the five touch- screen panels flashing colorful messages and pictures in seamless synchronicity. But first impressions fail to capture the promise, the complexity, and the meaningfulness of these two platforms, just as they fail to inform future efforts to provide similar spaces on other campuses.

Our individual experiences with our campus platforms, as well as our study of each other’s platforms, has illuminated some important lessons that we hope can facilitate future efforts. First, the location and design of the platform should not be an afterthought. Before placing chalkboards in a campus breezeway or digital panels on a building wall, it is important to think about the foot traffic and activity of the potential location, as well as the number and the layout of the boards or panels. Failure to imagine the space before constructing it will surely lead to wasted time and money, not to mention a weak first impression.

Second, support must be heavily considered. Whether low-tech or high- tech, these spaces require people to monitor and maintain them. At a bare minimum, it is necessary for chalkboards to be cleaned and for new questions to written on them after a determined amount of time. Similarly, digital spaces require human resources for troubleshooting technical issues, programming new questions, and maintaining or enhancing the code.

Third, it is wise to plan for marketing and programming around the space, especially for the launch. Just because the space is built does not mean that people will come. Be sure to market the platform and to plan exciting events to showcase the space and encourage participation. For example, a giant pizza party with giveaways was hosted to generate enthusiasm around the launch of The Wall.

Fourth and finally, much deliberation should surround the wording of questions. It is a mistake to underestimate the potential for question wording to encourage or discourage participation, as well as the degree to which it can promote certain types of responses (e.g., liberal or conservative, civil or hateful, serious or flippant). For example, after a few months, it was realized that for most of the questions posted on The Wall, the “Yes” response was most closely aligned with a liberal ideology.

Conclusion

College campuses have a responsibility to promote civil dialogue around important social and political issues. It is an important part, if not the most important part, of their larger mission to prepare students for their roles as citizens in a democratic republic. As our collective attention has been drawn to pursuing utilitarian ends and as institutional support has shifted to the so-called STEM disciplines, designating and designing campus spaces for meaningful dialogue can offer a powerful reminder of the civic mission of institutions of higher learning while concomitantly supporting that mission. When promoting civic engagement, faculty and campus leaders often tell students, “We don’t care how you vote. We just want you to vote.” In that same vein, “We don’t care how your campus promotes civil dialogue, we just want your campus to promote civil dialogue.” We hope this manuscript leaves you with both inspiration and practical ideas for doing just that.

References

Association for the Study of Higher Education. (2006). Research on outcomes and processes of intergroup dialogue. Higher Education Report, 32 (4), pp. 59–73.

Boyer, E. (1996). The scholarship of engagement. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 49(7), pp. 18-33

Campaign for the Civic Mission of School. (2011). Guardian of democracy: The civic mission of schools. Silver Spring, MD: Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools.

Cohen, C. J., & Kahne, J. (2012). New media and youth political action. Chicago, IL: Youth and Participatory Politics Survey Project.

Druckman, D. (2005). Doing research: Methods of inquiry for conflict analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Democracy Plaza. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://dplaza.usg.iupui.edu/

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., & Sorensen, N. (2011). Intergroup dialogue: Education for a broad conception of civic engagement. Liberal Education, 97 (2), pp. 46–51.

Harriger, K. J., & McMillan, J. J. (2007). Speaking of politics: Preparing college students for democratic citizenship through deliberative dialogue. Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation Press.

Hatch, J. A. (2002) Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Kahne, J., Middaugh, E., & Evans, C. (2009). The civic potential of video games. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Keeter, S., Zukin, C., Andolina, M., & Jenkins, K. (2002). The civic and political health of the nation: A generational report. The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement and The Pew Charitable Trusts

Kiesa, A., Orlowski, A. P., Levine, P., Both, D., Kirby, E. H., Lopez, M. H., & Marcelo, K. B. (2007). Millennials talk politics: A study of college student political engagement. College Park, MD: Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

London, S. (2010). Doing democracy: How a network of grassroots organizations is strengthening community, building capacity, and shaping a new kind of civic education. Washington, DC: Kettering Foundation.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Boss.

Schoem, D., & Hurtado, S. (2001). Intergroup dialogue: Deliberative democracy in school, college, community, and workplace. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Shea, D. M., Kovacs, M. S., Brod, M., Janocsko, K., Lacombe, M., & Shafranek, R. (2010). Nastiness, name-calling, and negativity: The Alleghany College survey of civility and compromise in American politics. Meadville, PA: Allegheny College.

The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement. (2012). A crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

van Hamel, A. (2011). From consumer to citizen: Digital media and youth civic engagement. Ottawa, ON Canada: Media Awareness Network.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Appendix A Democracy Plaza

Appendix B

The Civil Debate Wall

Appendix C

The Civil Debate Wall Website

Appendix D

Civil Debate Wall Mobile Website

Appendix E

“Are current gun laws insufficient in the wake of the Colorado shooting?”

Appendix F Analytics on The Wall

Author Biographies

Emma Humphries is the Assistant in Citizenship of the Bob Graham Center for Public Service at the University of Florida (UF), working to implement a three million dollar Knight Foundation Grant to prepare UF students to be informed, skilled, and engaged citizens. In addition to promoting student participation on The Wall, Humphries is currently developing a digital course in civic engagement to be piloted at UF in the fall of 2014. She recently completed her Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction with an emphasis in civic education.

A seasoned public affairs professional with expertise in digital outreach and social media, Shelby Taylor is the digital/communications director of the Bob Graham Center for Public Service at the University of Florida (UF). Taylor was the driving force behind creation of The Wall and has worked tirelessly to promote its use. She is currently working to develop a mobile website for The Wall, in addition to her tremendous responsibility for marketing the countless programs and public programs that the Graham Center has to offer.

Anne Weiss is the Graduate Assistant in Civic Engagement within both the Center for Service and Learning and the Office of Student Involvement at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), Indiana. Weiss is currently advising over ten student scholars dedicated to creating events for the IUPUI community based in advocacy, civic engagement, dialogue and deliberative democracy initiatives. In addition, Weiss is pursuing her Masters in Applied Communication (expected May 2013) with an emphasis on public dialogue and deliberation, while teaching and building a curriculum in training students to engage their community in freedom of speech, students’ rights and public dialogue.