Digital Storytelling: Augmenting Student Engagement and Success in Diverse Learning Environments

Eleanor G. Morris

Agnes Scott College

Tamra Ortgies-Young

Georgia Perimeter College

Author Note

Eleanor G. Morris, Agnes Scott College. Email: emorris@agnesscott.edu. Tamra Ortgies-Young, Georgia Perimeter College. Email: tamra.ortgies-young@gpc.edu.

Abstract

This paper presents the findings of a joint project in two very different political science classrooms. In both cases, traditional writing assignments were transformed to digital stories in order to increase student engagement, critical reflection, and media literacy, while still maintaining an overall emphasis on critical thinking and analysis, always important in the social sciences. The paper details the transformation of the two assignments to digital formats, presents survey data on the reception of the new assignments among students, and also discusses the strengths and weaknesses of these assignments in the college classroom. Overall, the assignments were well-received by students, and both professors felt the assignments realized all of the learning objectives. Critically, the assignments also contributed to an increase in digital literacy skills and a high level of student enthusiasm and satisfaction. Data indicates that the assignments were useful in generating early student engagement with political science and international relations majors and should be viewed as a possible tool to promote long-term student success and retention across diverse learning environments.

Keywords: media literacy, student success, retention, global citizenship, student engagement, digital storytelling

Introduction

As college professors, most of us are focused on two principal issues: how to ensure that our students learn the necessary content of our fields and how to foster learning beyond this specific content, in terms of life skills. It is this dual motivation that prompted some change to one of our traditional written political science assignments and, ultimately, generated this analysis and article. Many academic disciplines embrace writing assignments as a means to advance learning and enhance general educational outcomes that include improved writing, research, and analytical skills. Political scientists, in alignment with the common practices of the social sciences, assess student learning, at least in part, through written assignments—from the short article to the longer research paper. Given all of the attention that digital literacy has received in the scholarship of teaching and learning, we decided that it was past time to reinvent at least one written assignment in order to determine if students could attain the same level of critical reflection and analysis using a digital format. We also hoped to generate excitement among students to promote larger institutional efforts to foster student success and retention. If successful, we reasoned, we would have not only accomplished the specific assignment goals, but we also would have introduced a potentially new digital skill to our students, thereby preparing them not just for their next college course, but also for life beyond the classroom.

In order to situate our analysis, this paper first presents a review of some of the relevant literature on the use of technology to foster critical reflection and student engagement along with some information on the ways in which academic engagement fosters student success and enhances student learning. We then introduce our digital assignments and the ways in which they enhance reflection and global engagement for learners, especially for learners from the “millennial” generation. After a detailed discussion of our assignments and an assessment of them, we offer some concluding thoughts on assignment transformation. After employing this course vehicle, it is clear to us that the use of digital stories should be more widespread, as the digital format enhanced students’ digital literacy, augmented their critical thinking and analytical skills, and also generated engagement with course content, thereby enhancing student success and retention.

Media Projects, Critical Reflection, and Global Civic Engagement

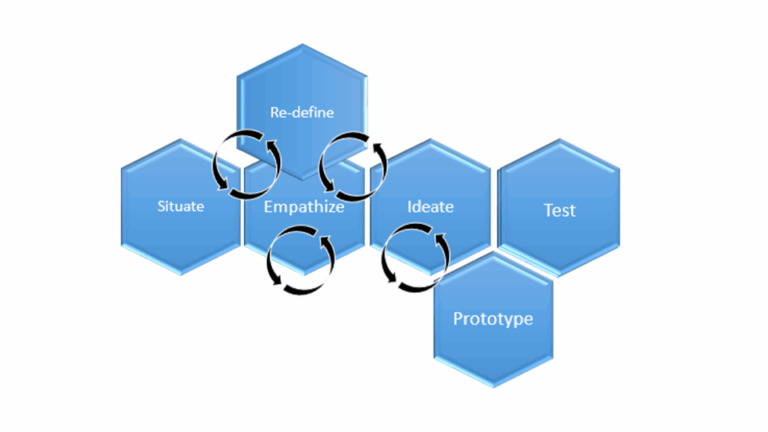

It is now common for instructors in a range of fields to comfortably use and promote a range of technologies in the classroom. However, while the main focus of this paper is on the application of a media project to political science or international relations course design, a brief discussion of the merits of critical thinking and reflection as a pedagogical tool to increase lasting global civic engagement is warranted to further explain the choice of digital storytelling as a primary assessment. Barr and Tagg (1995) in their landmark work on the shifting paradigm from teaching to learning argue that when contextual cues provided by the class disappear at the end of the semester, so does the learning. Barr and Tagg go on to emphasize this point by suggesting that in the learning paradigm, faculty are primarily the designers of learning environments that facilitate the best methods for producing learning and student success. Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning model provides a framework for understanding how students learn. Kolb found that learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. The experience of creating digital storytelling projects requires many deliverable components including phases for research, outline, script, execution, revision, and sharing. The nature of the project, therefore, provides students with the opportunity to find a deeper understanding of the material. In addition, the platform allows students a venue for making conceptual connections and applications with the global community. The intent is to lay the seeds for critical thinking, as well as lifelong engagement in civic and global affairs.

Supporters of Transformation Theory, an evolving theory of adult learning, suggest that beliefs must be tested through action (Mezirow, 1991). At this point, critical thinking and reflection become essential tools in the learning process (Mezirow, 1996). As students explore a deeper understanding of international affairs, the requirement to construct a digital story that provides a visual framework to course concepts forces students into a problem-solving dynamic that must employ a variety of learning styles simultaneously. The additional assignment caveat to tie the story to one issue, one country other than their own, or one social problem requires that students step outside their cultural frame of reference and see the problem in a global context, creating a new framework for engaged learning. Stimulating the development of generational cohorts of informed, engaged citizenry requires the practice of civic responsibility. Gottlieb and Robinson (2006) outline four essential civic competencies including intellectual, participatory, research, and persuasion skills that may be compatible with the broader goal of enhancing the critical thinking skills needed for effective citizenship.

Building healthy habits of critical thinking, reflection, and global civic engagement are educational objectives of the digital storytelling assignments. The desire is to provide the ideal environment for transformational learning while building healthy habits of civic engagement for the future. Research has found evidence that continuous reflection combined with active engagement leads to enhanced knowledge, skills, and cognitive development (Eyler & Giles, 1999). Additionally, Eyler (2002) suggests that when students share their conclusions through presentations in the classroom, other students are more likely to become engaged, resulting in more compelling conversations. Finally, Eyler argues that effective citizenship should not only be about interest and commitment but also should include the ability to analyze problems and engage in action. The decision to include a media project thus employs many tools of engagement by harnessing the interest of millennials in a semester-long media adventure, providing a platform for active learning and expanding the reach of the assignment through group discussion.

Providing an enhanced array of assignments such as media projects can lead to a more sophisticated and deepened understanding of course concepts and world view while also generating more student interest in and engagement with course materials. In order to inspire student engagement in a way that is transformational, research suggests that instruction must move beyond the traditional lecture format to a model that involves students in the learning process such as writing or problem- solving (Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 2006). Indeed, McKeachie’s research into teaching methods suggests that in order to create active learners, colleges must create vehicles that move beyond the transmission of knowledge (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2010). By engaging students with timely, active-learning activities, enhancing critical-thinking skills, and building global interest, media projects can serve as the spark to stimulate connections to engage students with their interconnected global world. Connecting students with meaningful activities is especially important in the first and second years of college when students generally connect with and select their majors. Indeed, experts suggest that students who are connected with a major early in their college careers tend to have higher levels of student success and persistence (Schreiner, 2009).

In order to maximize engagement, classroom strategies must connect with students at an emotional as well as intellectual level. For students to learn new information that may conflict with their existing theories of a social problem, it is essential that they be confronted with the problem in a context that requires analysis beyond a surface investigation; otherwise, they may retain their original understandings or misconceptions (Colby, Beaumont, Ehrlich, & Stephens, 2003). An essential part of designing educational experiences that provide transformative political engagement and foster critical thinking is being explicit in making the connections between the activity and the real-world political applications (Colby, Beaumont, Ehrlich, & Corngold, 2007). While it would be best if civic engagement were employed across the curriculum, it is difficult to mandate this curricular change in most institutions. However, individual instructors can design assignments that meet this goal (McCartney, Bennion, & Simpson, 2013). Digital stories provide a reflective catalyst for that transfer process.

While the method of harnessing civic engagement outlined in this paper has been employed by political scientists, the transformative properties of the activity lend itself to many disciplines. Serving the cause of civic engagement by placing democratic ideals and process in the core of postsecondary education is part of a national call to action initiated by the U.S. Department of Education. This call came from activities that culminated in a report published in 2012 entitled A Crucible Moment. After extensive dialogue with community stakeholders, The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement recommended that college activities be designed to prepare students to become informed, engaged, and globally knowledgeable citizens (The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement, 2012).

Comparing the Settings

Before turning to an examination of the assignments and their outcomes, it will be helpful to know a little something about the diverse environments in which we teach and the students with whom we interact. This is important, in part, because the academic environments in which our projects were assigned are very different and yet, the projects werereceived in similar ways by students. In addition, the pros and cons of the digital projects that we will discuss further in the article were virtually identical despite a rather stark difference in learning environments and student bodies. One college in which the project was assigned is a small private liberal arts college, while the other is a public two-year access institution. The small college’s student body is just under 1,000, mainly traditional students, one third of whom are underrepresented minorities. By contrast, the two-year college is an urban multi-campus member of a state university system with just over 24,000 students. The public college has a predominantly minority student body with a large contingent of first-generation immigrant students.

The Assignment at a Private Liberal Arts College

All of the students who received this assignment at the private liberal arts college were enrolled in an introductory course, Introduction to World Politics. This course requires students to follow and discuss current world events in order to better understand the ways in which global affairs are significant and relevant to their own lives. All of the assignments that students must complete for the course require that students relate, explain, and justify their own positions based on the knowledge that global interactions at the individual, community, and international levels are constant, necessary, and unavoidable. It is for all of these reasons that emphasis throughout the course is on making international politics personal for the students with the dual goals of prompting critical reflection and engagement as well as global citizenship.

In the Introduction to World Politics class, a state background paper assignment proved the best to convert to a digital-story format. This is generally the first assignment of the semester and is given to students after they have each selected a state to follow for the semester. In international relations, a state is considered to be the building block of the international system, and political scientists use this term to refer to what is colloquially referred to as a country. The state background paper is designed to get students to research information about their state and then to discern what they believe are the most important attributes in understanding their state as an international actor. Students must not only make hard decisions about what to include in their paper, but they must also thoroughly and convincingly explain the logic of their choices. Some of the types of issues that students may choose to include center around the following themes: international outlook; relationships with other states (major actors and/or neighbors); relationship with the United Nations; membership and participation in major international treaties; relevant contemporary history; social and cultural issues; population issues; political issues; health issues; and economic issues. In addition, students may choose to include an issue not listed above as long as they are clear about how and why that issue is critical to understanding their state as a current actor in the international system. Students are not given detailed instruction about issues that must be included or must be excluded in this assignment. Instead, they are expected to do enough detailed research to allow them to write comfortably and convincingly about three or four issues that they view as essential to understanding the actions and goals of their state. The assignment, when completed, should be between five and seven pages and be fully cited in compliance with MLA guidelines.

Not many changes were incorporated into the instructions of the assignment, as the goals of the paper and the digital story were the same. Instead of a five-to-seven-page paper, students were instead asked to create a five-to-seven- minute digital story. To accomplish this assignment, students were provided with information on how to find online tutorials for the digital storytelling assignment and one class session was set aside with the campus instructional technologist to provide students with basic information and some practice on how to work digital story programs, such as Photo Story and iMovie. While it is possible that the dedicated class session was not necessary for most, it certainly aided and alleviated fears for the few students who were nervous about using a technology with which they were largely unfamiliar.

In addition to the technical assistance described above, students received a rubric for assessment so that they would know in advance the types of issues that would be important in order to attain full credit for the assignment. The rubric (Appendix A) has four main categories: Project Purpose and Audience; Script Content; Technical Execution; and Credit. The first section, Project Purpose and Audience, assesses the extent to which students’ stories have a clear thesis that is supported throughout the assignment. Students make a thesis statement about the current climate in the state and then select issues to highlight and explain why and how the statement in their thesis is the most important one to know about that state’s activities in the current decade. Students who simply provide a broad overview of the state lose points as their story fails to be an in-depth snapshot of the geopolitics of the state. The second section, Script Content, is the section in which one is able to assess how engaging and well-written the content is. Here it becomes clear whether students took the time to write and edit their script before recording. If students do not pre-plan their script, it is quite obvious to the viewer, and ultimately the story gives very little detailed information about the state. The third section, Technical Execution, assesses the extent to which the story is technically well-done with clear images, helpful audio that enhances the story, and good editing. Finally, the Credits section of the rubric is where one examines the story to make sure each image is appropriately credited. In addition, students must attach a works cited page.

Having completed the assignment over the course of three semesters, it is clear to us that students had enough information to complete the assignment well if they were willing to put in the time and energy required to do so. On the day that the assignment was due, students were asked to upload it to our class webpage on Moodle. We invited students who were interested to show their stories to their classmates for the first part of class on the day the assignment was due. Taking the time to have a communal viewing of at least some of the digital stories seemed to create some class camaraderie and helped students see and understand something about other states in the global system.

Survey Results

For each of the semesters that students completed the digital-story assignment, they also completed a short survey after the assignment was submitted and before they knew their grade. For the three semesters, responses total 72. The chart below illustrates the responses and corresponding percentages to all of the questions provided in the survey. In addition, students had space on the survey to elaborate on their responses if they chose.

Table 1. Liberal Arts College Survey Results (Three Semesters)

|

Questions |

Yes |

No |

Yes and No |

No response |

|

Q1. Do you think that this project helped you understand the current international politics regarding your state? |

69 95.8% |

3 4.2% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

|

Q2. Did you ultimately enjoy creating this project in a digital-story format? |

49 68.1% |

14 19.4% |

8 11.1% |

0 0% |

|

Q3. Do you believe the digital format fostered your learning more than having to write a formal research paper on this topic? |

46 63.9% |

19 26.4% |

6 8.3% |

1 1.4% |

|

Q4. In addition to learning more about your state, do you believe that you also improved your digital literacy in completing this project? |

54 75% |

14 19.4% |

4 5.6% |

0 0% |

The data above show us that, generally, the digital story assignment was well received by students. Almost ninety-six percent believed that the assignment furthered their understanding of the international political issues of importance to their state. In addition, 75 percent of students believed that the assignment improved their digital literacy. These two results indicate that the assignment achieve its major goals.

The two other questions received less impressive results but also indicate a positive reception to the digital assignment. While almost 64 percent of students believed that the assignment fostered learning more than a traditional paper, this percentage is nonetheless striking. In general, the written responses indicated that students felt a real sense of satisfaction in completing the assignment. To complete the assignment well, students have to learn about a few issues within their state. They also have to justify and explain why they are highlighting some issues and not others; thus, they inevitably have to learn about a multitude of issues in order to make informed decisions about which to include in the final project. While this is true for the written assignment as well, the digital format provided students with the additional worry of how to present their issues in interesting, compelling, and creative ways. All of these challenges combined prompted hard work among students and, therefore, a real sense of excitement and satisfaction when the assignment was completed. Finally, the “public” piece of the assignment—putting it on Moodle for their fellow students to see—also made students accountable to a larger audience and therefore less willing to do the assignment poorly.

While the survey results offer one way to assess the utility of the digital story format, it is also illustrative to try to measure the extent to which the change in format prompted increased student engagement in the course and, furthermore, in the related fields of political science and international relations, majors that emphasize the importance of fostering civic engagement and global citizenship. To that end, one way to measure engagement in the course is to examine final grade- point averages for the three semesters with the assignment as a digital story compared with three semesters with the assignment as traditional paper. The average class grade percentage for three semesters before the assignment was transformed to a digital format was 79.8. By contrast, the combined percentage for three semesters with the digital- story format was 80.5. In this case, the difference in the class grade percentages is only very slight and could be attributed to a range of factors other than the difference in the type of assignment.

Using the digital assignment to generate enthusiasm for the course and to foster reflection and civic engagement was a goal of this project. While the difference in class grade percentages was slightly higher with the digital assignment, a more important indicator is the percentage of students who went on to become political science or international relations majors in semesters with the traditional paper versus those who went on to become majors after completing the digital story assignment. In this case, the results are striking. Thirty percent of students who completed the traditional paper assignment went on to become political science or international relations majors. By contrast, 45 percent of the students completing the digital assignment went on to become majors. By any measure, this is an impressive change and demonstrates the extent to which technology can foster reflection and civic engagement in students. Early engagement and excitement within majors plays an important role in student success and retention.

The Assignment at a Two-Year Public Access Institution

All of the students who received this assignment at the public-two year college were enrolled in a common core course, Global Issues. This course requires students to follow and discuss current world events in order to integrate these concepts into their understanding of their place in an interconnected world. All of the assignments students complete for the course require that they apply course concepts to global events and/or issues while discovering relevance in their lives. Like the course at the private institution, the emphasis in on making politics personal in a global setting.

Students in the Global Issues class were required first to write a global issue background paper in the early part of the term to examine and explain one important international issue from among topics including globalization, human rights, terrorism, global inequality, environmental issues, and cultural conflict. Students were encouraged to begin with the textbook and move out into scholarly and contemporary sources to find information for the paper. This research laid the foundation for script development for the subsequent digital storytelling assignment. Students were required to prepare for the assignment by creating a two- column script, which required them to align images with academic content while documenting sources. In-class training for the technical aspects of the project including the fundamentals of two-column scriptwriting and Microsoft Photo Story software and editing was provided by personnel from the College MediaSPOT, a specialized multimedia lab system.

The digital story assignment was also an integral part of a semester-long service-learning project designed to enhance civic engagement and promote civic- learning outcomes. The course design included a service-learning project that required students to work in teams to conduct a textbook drive for an adopted university in Nigeria. The course plan included a partnership with a local Atlanta not-for-profit community group for Nigerian immigrant professionals from The Institute for Anambra Development (TIFAD). This group is dedicated to service in their home state of Anambra, Nigeria. Members of TIFAD came to the class to lead discussions on the application of course concepts on global matters in Nigeria.

For the digital story project, students expanded on the global issue background paper they had already written and transformed it into a digital project. The project’s educational goal was to allow students to apply their knowledge of their selected global issue to the Nigerian case. The final step was to connect the research to the Anambra State University service-learning project to enhance engagement and learning while giving a greater purpose to the textbook drive. This effort to “think globally but act locally” was designed to inspire a deeper understanding of course concepts while sparking global engagement.

When conducting research on their global issue and on the application of the issue to Nigeria, students were encouraged to go beyond the requirements of a traditional research project to reach the multiple connective goals of the assignment. The multiple phases of the project facilitated the development of critical thinking, writing, and skills while building media literacy. The digital story technical requirements enhanced life skills including organizational and computer competencies. The final general educational outcome for this project was the transformative connections provided by civic-learning opportunities. The bonds that developed between the TIFAD visitors and the class created community at the local level that spanned the distance to Nigeria and around the globe.

Students provided a final-cut presentation of their digital stories to their classmates over two consecutive class periods. Class discussion followed each presentation to explore the issues further and to provide a group critique of the presentations. Staff from the MediaSPOT attended the screenings and provided feedback. Students voted on their two favorite digital stories and those were presented at the culminating service-learning celebration with the representatives of the TIFAD leadership. Feedback from the community partners was very positive, and requests were made of those students to consider sharing their videos through the TIFAD website to promote awareness of global issues and to advance TIFAD’s philanthropic goals. In the end, students collected over 2,000 books and digital materials for the TIFAD partners and the project has been successfully replicated at a sister campus and has been adopted by other colleges in the area.

Students were provided with rubrics for the research paper and the final digital-story project. The rubric for the media project was identical to the rubric provided to the private college students for the purposes of this study. As stated above, the sample rubric is provided in the appendix of this paper.

Survey Results

Data for the two-year school are available for one term and presented in the table below.

Table 2. Public Two-Year Institution Survey Results (one term)

|

Questions |

Yes |

No |

Yes and No |

No response |

|

Q1. Do you think that this project helped you understand the current international politics regarding your state? |

15 71.4% |

6 28.6% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

|

Q2. Did you ultimately enjoy creating this project in a digital story format? |

18 85.7% |

3 14.3% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

|

Q3. Do you believe the digital format fostered your learning more than having to write a formal research paper on this topic? |

17 80.9% |

4 19.1% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

|

Q4. In addition to learning more about your state, do you believe that you also improved your digital literacy in completing this project? |

18 85.7% |

3 14.3% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

As the table illustrates, those who had a positive view of the project responded that the project was fun and interactive, and the format required more in-depth learning and provided greater understanding of the topic. They also liked learning from classmates’ projects and suggested that visual learning had advantages. Finally, some students liked that the project focus on Nigeria. Those that did not have a favorable view of the project believed they already were well versed on their chosen global issue, did not like the tie to Nigeria, thought Microsoft Photo Story software was too limiting in its capabilities, or thought that a formal paper would be a better learning venue. Seventeen of 21 respondents suggested that they believed they learned more from the digital storytelling format. Comments in support of the format included that it was enjoyable and creative; the project spanned the distance to Nigeria; the project forced students outside their comfort zone; and that learning was captivating, more personal, and more in-depth. Comments from students who did not favor the format suggested that it was more difficult to execute than a traditional paper. Students overwhelmingly responded that they enjoyed creating the digital project.

The survey recorded student responses to an inquiry about whether the project increased media literacy. Just over 85 percent of the students believed the project improved their media literacy and those who disagreed said they were already accomplished in computer skills. Students were also asked an open-ended question about the strengths and limitations of the assignment. Comments included that transforming research into a script appropriate for a digital format was the hardest part of the assignment, that they wished the software was available for Macintosh computers, that the project was a creative outlet, and that they would recommend it going forward.

While the survey results suggest that students found the alternative media assignment engaging and relevant, additional research into final class grade percentages suggests that the assignment may have contributed to better final outcomes. The assignment was used in a 2010 section of the Global Issues class. When the class was offered again a year later, the course design did not include an individual digital story project. Comparing the class grade percentage of 3.17/4.0 in 2010 to 3.06/4.0 in 2011 supports the private college’s results the overall class average dropped only slightly without this assignment in the mix. However, a follow-up study of students in the digital assignment class found that 61 percent went on to major in political science or criminal justice (both in the same department) in 2010, while only 54 percent of those in the class without the digital assignment ended up these majors. When combined with the results from the private college, the data indicate that the digital story assignment provided a more personal exploration of global issues, which seemed to enhance student learning and engagement, as predicted by the literature.

A recent examination of teaching civic engagement best practices suggests that this study incorporates some of the hallmarks of the scholarship of teaching and learning in political science (McCartney, Bennion, & Simpson, 2013). Two instructors conducted this study at two very different institutions. The study was conducted over successive terms with different student populations. The assessment contains student surveys, class grade averages, and data on major choices. Finally, we applied relevant literature to the project to form a proper context for analysis.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

Overall, instructors at both institutions feel that digital projects have a place alongside other pedagogical tools to promote student engagement, global citizenship, and student success. Our experiences in the classroom provided both qualitative and quantitative evidence that students find media projects creative and useful. As the literature has shown, experiential learning that combines meaningful course objectives, critical thinking and reflection, and engaged active learning produces deeper understanding and may lead to a lifelong connection to learning outcomes. As political scientists, the essential additional general learning outcome of civic engagement is also a paramount concern in course design. Media projects can enhance civic and global connections by removing the walls of the classroom and placing students at the crossroads of the global community while also improving media literacy.

The digital story project and subsequent class discussions of each project allow for an exploration of information on international affairs while providing a research opportunity through the construction of scripts and search for accompanying media components such as music and images. All of this combines to provide an ideal learning platform. The option of class discussion of the media projects can add a final component to validate student work, increase accountability, and deepen the learning experience.

A comparison of data collected at both institutions revealed overwhelming student support for the digital assignment format. Students at both colleges also affirmed the project’s learning objectives of increased knowledge of international affairs and enhanced media-literacy skills. A majority of students at both schools indicated that they believed the digital assignments were preferable to a standard term-paper assignment, although the results showed a higher level of support at the two-year public than at the private liberal arts college. The research presented in this paper suggests that this digital media assignment is a good fit for institutions serving diverse student populations and missions and can be a key tool in fostering student engagement and success.

A critical assessment of individual media projects at each institution coupled with a comparison of the assessment tools across the two institutions leads to the following conclusions:

- Media projects are an engaging assessment activity that provides a creative alternative to the standard research paper in the political- science classroom, with particular appeal to the millennial student.

- The multi-step, multi-media nature of media projects provides an active learning platform for adult learners, possibly enhancing learning outcomes for this demographic group.

- Adding class discussion of the media projects can further learning for class participants and provide the final step of critical reflection for the learner-presenter.

- Students from demographically very different institutions reported that the assignment helped expand their learning in international affairs and did so in a more engaging way than a traditional research paper.

- Students from both institutions reported that they enjoyed the assignment. A positive learning experience aids in imparting course learning objectives but may also lead to the development of a lifelong interest in civic and global affairs.

- An added general-education outcome of enhanced media literacy makes the assignment appealing to students and facilitators. Student anxiety about technical skills should be addressed by technical training as part of the course vehicle.

- Implementation of media assignments requires special care in designing technical support and facilitation of deliverables on a timeline for optimal learning outcomes, particularly for students from at-risk populations.

- Students suggested on the survey that the media assignment dramatically increased their interest in civic issues and international affairs.

- Detailed instructor guidance on assignment expectations and process are key to making sure students reach the depth of understanding required for transformative critical reflection.

- Students from both institutions connected with media assignments in a way that appears to have fostered student persistence and success. Preliminary evidence of this finding is reflected in the student surveys, the class grade averages, and the major conversion averages.

Suggestions for future research in this area include a wider survey of student attitudes towards the project and additional studies on the long-term outcomes on global civic engagement. While, as we have stated, both projects were used in political science classrooms, we believe that the digital story may offer students and professors in a range of social science disciplines the opportunity to try something new in a relatively stress-free way that enhances the learning experience. Finally, and perhaps of paramount importance to teachers and administrators, the findings presented here about the extent to which a digital story assignment can generate increased student engagement and success merits much enthusiasm and should be seen as a call for more exploration of such assignments across the curriculum.

References

Barr, R.B. & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change. 27(6), 12-25.

Colby, A., Beaumont, E., Ehrlich, T., & Corngold, J. (2007). Educating for democracy: Preparing undergraduates for responsible political engagement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Colby, A., Beaumont, E., Ehrlich, T., & Stephens, J. (2003). Educating citizens: Preparing undergraduates for lives of moral and civic responsibility. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Eyler, J. (2002). Reflection: Linking service and learning-linking students and communities. Journal of Social Issues. 58(3), 517-534.

Eyler, J. & Giles, D.E. (1999). Where’s the learning in service-learning? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gottlieb, K. & Robinson, G. (2006). A practical guide for integrating civic responsibility into the curriculum. Washington, DC: Community College Press.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2006). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom (3rd ed.). Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

McCartney, A., Bennion, E., & Simpson, D. (2013). Teaching civic engagement: From student to active citizen. Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association.

Mezirow, J. (1996). Contemporary paradigms of learning. Adult Education Quarterly. 46(3), 158-173.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimension in adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rogers, R. ( 2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education. 26(1), 37-57.

Schreiner, L. (2009). Linking student satisfaction and retention. Iowa City, IA: Noel-Levitz.

Svinicki, M. & McKeachie, W. (2010). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012). A crucible moment: College learning and democracy’s future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Additional Resources for Designing Student Media Projects

Center for Digital Story Telling

Microsoft in Education – Teaching Guides

www.microsoft.com/education/en-us/teachers/guides/Pages/digital_storytelling.aspx

Video Tutorials

http://mediaspot.gpc.edu/faculty.

Appendix

State Story Sample Rubric

Student’s Name: Date:

|

CATEGORY |

Excellent 13.5-<15 |

Good 12-<13.5 |

Fair 10.5-<12 |

Poor <10.5 |

|

Project Purpose & Audience |

Establishes a purpose early on and maintains a clear focus throughout. It is clear that the author has identified several major issues to examine about the selected state and this focus is maintained throughout. In addition, evidence is given for why these issues are the most important for understanding the selected state today. Students can clearly explain why they felt the vocabulary, audio and graphics chosen fit the issues identified. |

Establishes a purpose early on and maintains focus for most of the presentation. Some awareness of issues and logic to the selection of the issues but this focus is not maintained throughout. Students can partially explain why they felt the vocabulary, audio and graphics chosen fit the target audience. |

There are a few lapses in focus, but the purpose is somewhat clear. Issues and logic are present but not maintained consistently. Students find it difficult to explain how the vocabulary, audio and graphics chosen fit the target audience. |

It is difficult to figure out the purpose of the presentation. Limited awareness of issues and/or logic to their selection. |

|

Script Content |

Content is engaging — viewer is left with thought-provoking ideas. Script is compelling and well written — concise use of words to make important points. Emotional dimension of the piece matches the story line well. Viewers are encouraged to care about the topic, person, organization, etc. |

Content is interesting — viewer is left with thought-provoking ideas. Script is well written — makes important points. Emotional dimension of the piece somewhat matches the story line. |

Content is spotty and, at times, difficult to follow. Some surprises and/or insights. Script is adequately written, but sometimes is confusing. Emotional dimension of the piece is distracting (over the top) and/or does not add much to the story. |

Not very interesting or clear. Script is difficult to understand & the point is unclear. Emotional dimension of the piece is inappropriate OR absent. |

|

Photo Story Technical Execution:

|

Voice quality is clear and consistently audible throughout the presentation. If music is used, it enhances the piece, matches the story line, and does not overpower the voice. Illuminating: Images create a distinct atmosphere or tone that matches the issues selected to highlight. The images may communicate symbolism and/or metaphors. The |

Voice quality is clear and consistently audible throughout the majority (85- 95%) of the presentation. If music is used, it matches the story line and is not too loud. Interpretive: Images create an atmosphere or tone that matches some of the issues |

Voice quality is clear and consistently audible through some (70- 84%) of the presentation. If music is used, it is not distracting — but it also does not add much to the story. Illustrative: An attempt was made to use images to explain issues but it needed more work. Image choice is |

Voice quality needs more attention. If music is used, it is distracting, too loud, and/or inappropriate to the story line. Inappropriate: Little or no attempt to use images to demonstrate the major selected issues of importance to |

|

meaning of the story is transformed by the use of images. The pace (rhythm and voice punctuation) fits the story line and helps the audience really “get into” the story. |

selected to highlight. The images may communicate symbolism and/or metaphors. The story relies on images to convey meaning. Occasionally speaks too fast or too slowly for the story line. The pacing is relatively engaging for the audience. |

mostly logical but, at times, confusing (i.e. not explained) or merely decorative Tries to use pacing, but it is often noticeable that the pacing does not fit the story line. Audience is not consistently engaged. |

the state. Images interfere or are at cross- purposes with the story’s meaning. No attempt to match the pace of the storytelling to the story line or the audience. |

|

|

Credit |

All people, organizations, quotes, ideas, music, and contributors are appropriately credited. Permission has been obtained (or Creative Commons license information provided) for images and audio not created by the author. |

Most people, organizations, quotes, ideas, music and contributors are credited. Might not include permission or provide license information. |

Some people, organizations, quotes, ideas, music and contributors are credited. Might not include permission or provide license information. |

Few or no people, organizations, quotes, and contributors are credited. |

*This rubric has gone through several revisions by different users but is based on versions/content provided in:

- Digital Storytelling Cookbook, 2007, by Joe Lambert. Center for Digital Storytelling. Digital Diner Press.

- Digital Storytelling Tips & Resources, 2008, by Gail Matthews DeNatale. Simmons College. Boston, MA.

- A presentation at the Governor’s Teaching Fellowship Program in 2010 by Patricia Dixon, of Emmanuel College, Franklin Springs, Georgia.

- A presentation at The Gulf South Summit on Service-Learning and Civic Engagement in 2011 by Tamra Ortgies Young, Georgia Perimeter College, Atlanta, Georgia.

Online format: http://millie.furman.edu/mll/tutorials/photostory3/index.htm

PDF for those who want something they can print out: www.jakesonline.org/photostory.pdf

YouTube video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0oH9qE9qEY

Author Biographies

Dr. Eleanor Morris is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Agnes Scott College, a liberal arts college for women in Decatur, Georgia. She also directs the International Relations program at the college and is the faculty adviser for the Model United Nations Club. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and her master’s and doctoral degrees in political science from Georgia State University. In addition to teaching classes and conducting research in international relations theory and European politics, she is also interested in the research of teaching and learning with technology to promote student success.

Tamra Ortgies Young is an Instructor at Georgia Perimeter College, a two-year unit of the University System of Georgia located in greater Atlanta. Young earned a Master of Public Administration and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science at Iowa State University. Passionate about student engagement and civic education, Young is a member the Georgia Political Science Association Executive Board and serves as the Teaching and Learning Coordinator. A member of the Dunwoody Great Decisions Lecture Series Executive Board, she will serve as the 2014 Program Chair for the largest Great Decisions Lecture Series in Georgia. Young met her co-author Dr. Eleanor Morris when they were honored with Georgia Governor’s Teaching Fellowships in 2010 at the University of Georgia.